New Wave German Rap: Diversification of The “Hood” as a Device for Performing Citizenship(s) in Berlin

Carlotta Lazarus [Email] [LinkedIn]

Berlin's urban fabric exemplifies a mosaic of distinct neighborhoods shaped by historical confluences of independent towns and the enduring imprint of the city's East-West division during the Cold War. This essay explores how Berlin's uneven spatial development reflects the broader Lefebvrian notion of space as socially produced and inherently ideological. It positions rap music as an analytical lens to examine urban experiences, drawing on the genre's spatial traditions and its evolution in Berlin's "New Wave" scene. By analyzing the lyrics and visuals of three prominent New Wave artists—BHZ, Pashanim, and Teuterekordz—representing Schöneberg, Kreuzberg, and Prenzlauer Berg, respectively, the essay underscores how rap narratives articulate the diverse realities of Berlin's built environment.

This study investigates the interplay of local histories, social dynamics, and artistic expressions within Berlin's Kieze. It argues that rap music not only represents but actively shapes perceptions of urban precarity, identity, and power. The findings reveal the genre's potential as a cultural tool for understanding the lived spatialities of contemporary cities and contribute to broader discourses in urban anthropology and geography.

Introduction

Berlin’s urban topography is uniquely characterised by locally distinctive districts and neighbourhoods, which follows from a regional history of several independent towns having grown together into one. Accordingly, the city today represents a mosaic of interwoven, yet uneven urban development, with locally specific governance, economies, demographies, and conflicts. Until 1990, another dimension of difference in Berlin’s developmental palimpsest has been its 45 year long division into East and West, the lasting impact of which cannot be overstated. Since 2001, Berlin is administratively subdivided into 12 districts, consisting of smaller neighbourhoods (“Kiez”). Departing from a Lefebvrian understanding of space as socially produced, a city with a society and history as rich and diverse as Berlin will consequently produce an accordingly uneven “glocalised” space (1991). The experience of such a Lefebvrian space is reflected in the cultural products of its inhabitants, in line with an understanding of popular culture as infused with the political.

A cultural studies approach to urban development is thus of interest to the field of anthropology, as it adds to an understanding of how residents shape, share, and resist the space. Within cultural urban studies, an underexplored lens is the musical genre of rap (Seeliger&Dietrich 2017). The premise of rap as an analytical prism for the urban experience is its inherently spatial tradition, drawing on spatial narratives in its very genesis from peripheral neighbourhoods in 1970s New York. A foray into the spatial imaginations and references in rap, traditionally with the narrative aim of representing the personal “hood”, “street” or “block”, thus promises contributions to the field of urban studies and geography more widely (Seeliger&Dietrich 2017).

Departing from the rise of a New Wave in German rap, this essay will begin by situating the study in urban and cultural anthropology. It will then investigate three different Berlin New Wave case studies: BHZ, Pashanim, and Teuterekordz representing the Kieze of Schöneberg, Kreuzberg, and Prenzlauer Berg, respectively . In doing so, this essay will demonstrate the multifunctional potential of rap music to provide anthropological insights into the uneven localities of contemporary urban experiences.

CONTEXT

In a Lefebvrian understanding of the city, urban space is socially produced, and thus never apolitical but ideological. This production of space is determined by the uneven distribution of power throughout society, manifesting spatially across dimensions like housing, development policy, and struggles between police authority and minorities (Forman 2002). With the spatial turn in the 1980s, scholarly interest has been directed at spatial practices, the co-constitution of space and culture (Lefebvre 1991). A spatial reading of rap practices thus matters as linguistic representations of urban terrain describe perceived social realities, fears, and desires with material implications for actual behaviour (Harvey 1993).

In cultural studies, products of popular culture have been understood as expressions of everyday practices, social status, lifestyles, and world views, but also as a political struggle for representation and symbolism, a medium for criticism and reproduction of social inequality (Scharenberg 2001). Sociocultural engagement with rap has been considered a promising research mode for on-the ground understandings of urban precarity, perhaps more unfiltered than a strict focus on conventional political discourse would allow (Seeliger&Dietrich 2017).

Rap’s emergence as a musical genre, and rise to commercial success in mainstream youth culture can be located in New York’s Bronx in the early 1970s (Bennett 1999). This local context is vital for understanding the cultural role of rap, and the ways it is re-appropriated and reclaimed as a means for collective expression and empowerment until today. As a response to their marginalisation in a systematically neglected, racially and socially segregated neighbourbood, the product of urban renewal strategies, rap developed as a musical way to express the precarity but also pleasure of black urban life often performed at “block parties” in the “hood” (Munderloh 2017). As a highly visible and audible creative movement, literally from the streets, it thus carried power as a unifying device for a marginalised community, representing collective experiences of social and political exclusion, but also pride in and identification with being “toughened” by the ghetto (Bennett 1999). As Beadle (1993) describes, rap became the “vehicle for pride and for anger, for asserting the self-worth of the community”. It is this origin making rap at once so political and spatial in nature. From then on, the ghetto has remained and intensified as a key source of identity in commercialised rap productions, which increasingly gained ground as the genre’s spirit of protest, pride and people travelled beyond the Bronx (Munderloh 2017).

US hip-hop culture first reached Germany in the late 1980s and was recognized by German migrant youth, who drew parallels to their own ethnic identity, as well as white middle-class youth who resonated with the sentiment of breaking free from societal (and parental) pressures (Munderloh 2017). Despite a German rap scene having since flourished to one of the country’s most dominant youth cultures, there remains ambiguity regarding the identity of German rap, but can at present best be identified by language (Loh& Güngör, 2002). One reason for German rap’s identity struggles can be found in the fact that by the time of hiphop’s arrival, Germany did not suffer from the same urban malaises of ghettos, segregated neighbourhoods and racialised poverty that the US did (Buß 2002). Thus German rap has never been truly able to speak authentically from the "ghetto”. While this is not to aquit Germany from its urban issues, it does have a comparatively strong welfare system and rappers’ narratives are often, while rooted in truth (an immigrant or East German background), artistically exaggerated. Especially in the early 2000s the genre adopted US-style Gangsta elements, readily taking up the tradition of drawing a strong sense of identity from a locale - in Berlin, naturally the Kiez (Seeliger&Dietrich 2017).

In the past 5 years, mainstream German rap has increasingly moved away from Gangsta rap and towards a formerly underground "New Wave" subgenre, characterised by experimentation and a disregard for conventional genre “rules” (Barth 2022). Moreover, New Wave seems to unite separate worlds – with cross-generation collaborations, cross-genre references and seemingly effortless but highly curated visual aesthetics (Barth 2022). In tradition with the 1970s origins of rap, the urban narrative modes in the New Wave are heavily influenced by the local contexts they emerge from. The emergence of New Wave German rap promises an underexplored research avenue, having so far been acknowledged little academically (Barth 2022) and only marginally in popular journalistic writing (Krämer 2021), and even less so in relation to the built environment. It can be reasonably suspected that with a new era of German rap comes a new era of spatiality in rap texts and visuals. The bold new production techniques and mentalities within New Wave consequently allow for more diversity in styles, sound and themes. As this essay will show, such genre diversification has brought about a corresponding diversification in the ways the built environment features in them. This positions the New Wave as a most contemporary product in which experiences of socially produced space are culturally manifested, and beg for an evaluation in their own right.

Methodology

Three New Wave artists were chosen based on their association with separate neighbourhoods, popularity and relevance in the industry. Individual songs were chosen based on thematic relevance. Lyric analysis followed a discourse analysis approach, using qualitative coding and annotation for spatial and political themes. Interpretation was informed by production contexts and local history and politics in secondary literature.

BHZ: Loitering on Streets but no Gangsters

BHZ, a rap collective of 7 artists from Schöneberg, represents the New Wave spirit through a genre- bending sound of carefree, uneventful summer nights with friends. Crucial for conveying this atmosphere is the setting of Schöneberg (postcode 62), the Kiez BHZ met in as teenagers and started rapping from. Schöneberg is a popular southwestern residential area, known for its historical architecture, cultural scene, independent shops, and vibrant street life (Figure 1-2, Stadt Berlin, 2024). As a charming middle-class neighbourhood embodies BHZ’s down-to-earth themes and style well, who have previously criticized other rap in their songs “the whole scene is stuck up/ you only rap about money and bitches, digga, get a grip” (“Schließe die Augen”). BHZ’s spatial modes of narration evolves strongly around authenticity validated via their attachment to the neighbourhood, but in a different manner to the Gangsta rap tradition- as they disclaim in their most streamed song “Flasche Luft”: “we’re loitering on the streets but we’re not gangsters”. At the core of this local attachment is simply hanging out drinking and smoking at Apostel-Paulus-Church, the group’s preferred meeting spot featuring numerously in their texts (Figure 3).

Figure 1: Map of Schöneberg’s location in Berlin. Source: Wikipedia (2024).

Figure 2: Picture featured on Berlin’s official website for Schöneberg. Source: Berlin.de (2024).

Figure 3: BHZ in front of Apostel-Paulus Church in Schöneberg, Berlin. Source: Juice (2019).

With their self-proclaimed goal of putting Schöneberg on the map, BHZ’s texts rarely venture into criminal or political territory, attributable to the relative absence of social issues in the neighbourhood, especially compared to Kreuzberg and Prenzlauer Berg who seem to have prompted more critical stances. BHZ’s connection to the city is mainly based on friendly familiarity with cornershop owners, aestheticization of public alcohol consumption and reminiscence of an idle middle- class youth turned rap career: “we’re spending our time here in the Kiez/our toys: mic and the beats/ what’s up this is our Berlin” (“Hoodparadies”, 2016) or “meet the boys, hood nights, and poison in cup/good mood, good vibes and some laugh fits” (“Hoodnights”, 2021). Cornershops, park benches and churches are the New Wave nodal points in Schöneberg (Figure 4-5). The wholesome affection for their neighbourhood is expressed in considerate sentiments like “Off to hobo park, let’s roll another blunt/ no problem, there’s no kids playing in the sandbox” (“Hoodparadies”, 2016), or friendly shoutouts to neighbourhood characters like “hanging in the pub and Tina pours me Korn” or “I get an Uludağ and Döner from Rüyam” (“Hoodnights”, 2021) (Figure 6-7). This open fondness reflects their stable social background, just like the aggression of gangsta rap is attributable to precarious backgrounds, as a result of which BHZ’s inclusive local patriotism is mostly stylistic (rather than deterrent) in nature.

Figure 5: BHZ in front of a cornershop on Hauptstraße, Schöneberg. Source: Youtube (2021)..

Despite a less tumultuous history, Schöneberg has recently experienced gentrification, bringing changes that BHZ see as both the frame and departing point for their work. BHZ processes and counters these changes with a nostalgic mode of spatial narration – the streets are not the location of criminal gang activity and public nuisance but for remembering humble nights past, drinking beer with friends: “to the hood, I want to live here til eternity/to the boys who were at the church back then/ before the young’uns came, when so much was different” (“Hoodparadies” 2016), “Always at the corner with the boys, didn’t learn much/ and when I’m gone, the church stays in my heart” (“Church”, 2021) or “3-0 to 6-2, we were kids (...) and everything around me changes today” (“3062” 2019). This is about as explicit as it gets though, and overwhelmingly, Schöneberg as a prosperous middle-class background setting dominates in an absence of any desire to “escape” the hood. Unlike rags-to-riches gangsta rap narratives, it romanticises drunken public transport journeys and professes “everything so good in the hood, yes I’ll stay here/ everyone’s making their money, no one’s getting stingy” (“Flasche Luft”, 2020) or “Always at the church, digga, we smoke spliffs/ I have everything I need, I don’t need to get away” (“3062”, 2019) (Figure 8). On the contrary, despite their newfound commercial success, BHZ express a desire to be back in Schöneberg all the more: “Thinking back to the time in the hood/ we were here, always amongst us/today we tour through the country with the boys/ deals come in but I decline” (“3062”, 2019).

A melancholy present in BHZ’s texts is rooted in a desire for their neighbourhood to stay the same, whereas the Gangsta speaks from a need for change: “long nights, sitting in an Uber to Schöneberg/share a cig and my heart gets warm/day out the same shit with the gang/yes, man you know where I hang” (“Church”, 2021) or “back then Schöneberger young kids, looked up to the bigones (...)/no didn’t need much, a kofta was enough/ today worries are big, look mum I want a lot/ summer 2013 it started with 7 gang/BHZ 2-8-2-6, ink stays lifelong” (“Regen Prasselt”, 2020).

BHZ’s unique style of localising carefreeness, nostalgia and deep affection in Schöneberg can thus be seen as an updating and recontextualising of the mythical tough and precarious “street” in a contemporary New Wave age of rap by singularising their new middle-class lifestyle in contrast to the figure of the Gangsta.

Pashanim: Between Istanbul and Kreuzberg 61

Pashanim represents the New Wave with signature tales of everyday life as a drug dealer in his home neighbourhood Kreuzberg. Pashanim’s mode of spatial narration is characterized by his German- Turkish migrant and diaspora identity, substance economies, and conflicts with the police. Pashanim’s texts are embedded in and reflective of not only post-War urban renewal politics but also the neoliberalist influence on migrant strategies for survival and identity formation.

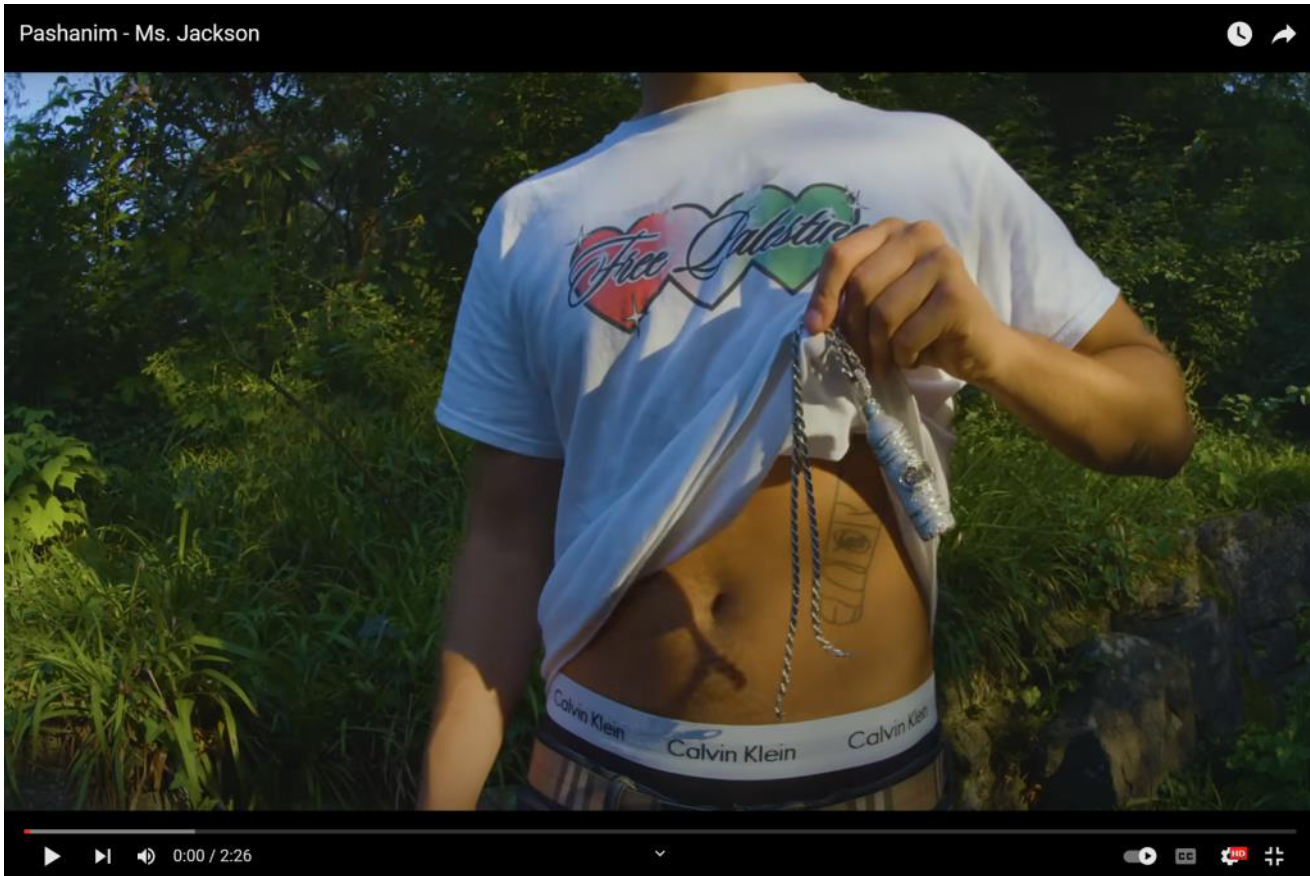

Pashanim’s auto-ethnographic account is situated in Kreuzberg as Berlin’s centre of ethnic communities and alternative lifestyles, including punk and leftist squatter movements. This is rooted in post-War labour policy, when Germany’s economic growth required additional labour, resulting in a labour recruitment agreement between various European countries, including Turkey, in 1961 (Güney 2017). Kreuzberg as the desolate margin of West-Berlin, surrounded by the Berlin wall on three sides (Figure 9) and neglected by urban renewal policy, provided the cheap housing stock these “guest workers” were looking for, which soon led to Kreuzberg being recast as an immigrant “ghetto”, a reputation that lingers today (Lang 1994). In reality this designation comparing Kreuzberg to Harlem lacked in understanding and awareness of such terminology’s historical and political dimensions, and was driven mainly by alarmist and racialised media discourse (Güngör& Loh, 2017); Pashanim humorously picks this up in “Airwaves” (2020) warning “you think you’re getting mugged when you see one of us” or “police know our songs, 61, Berlin-Bronx” cheekily referencing hiphop’s origins. With many originally “temporary” migrant workers settling down as permanent citizens, Kreuzberg’s status as a Turkish diaspora enclave solidified (Dell 2021). Second-generation German-Turks developed their own infrastructure in Kreuzberg, including Turkish shops, mosques, bars, linguistic landscapes and in the face of rising unemployment, this was a niche readily used to build an economic existence within Germany (Figure 10-11) (Özüekren&Ergoz-Karahan 2010). Kreuzberg thus became a diasporic thirdspace between Turkey and Germany to maintain their transnational identities within its own web of social institutions, norms, values and language (Özüekren&Ergoz-Karahan 2010). Pashanim’s texts are littered with references to this “little Istanbul” e.g. “every bench in my area full with Çekirdek” (“Airberlin” , 2023), sunflower seeds, a common Turkish snack whose inedible husks are traditionally dropped on the ground) or frequent mentions of the Turkish water brand “Saka” sold mainly in Kreuzberg: “Walking through 6-1 in Prada’s and Saka water tattoo” (“Airwaves”, 2020) (Figure 12).

Figure 9: Map of Kreuzberg’s location West and East Berlin. Source: Institute of European History (2004).

Figure 11: Turkish linguistic landscape at a Kreuzberg housing estate (engl. “Kreuzberg Centre”). Source: Wikipedia (2024).

Figure 10: Turkish Shops in Kreuzberg in 1983. Source: German Information Centre (2024).

Figure 12: Transnational symbolism in Pashanim’s music video to “Ms Jackson”: “Free Palestine” shirt, “Saka” water tattoo and necklace. Source: Youtube (2023).

After reunification, Kreuzberg found itself at the new city centre, and saw its dishevelled image converted into a colourful underground-chic one. However, this myth of Kreuzberg not only exposed it to external pressures, like racist attacks from the East and gentrification, it also inadvertently disguised its deficiencies, serving as a “psychosocial antidepressant covering up real social fractures” (Lang 1994). The precarious reality of Kreuzberg’s population is not least owed to shortcomings in German integration strategies, lacking comprehensive educational, economic and social efforts and systematically (re)producing a parallel society of immigrants along socioeconomic and educational differences with spatial implications for housing and mobility (Kahraman 2014). In “Draußen essen spät schlafen” (2023) Pashanim recalls such social ills as “I used to climb over junkies on my way to school” and mentions generational history in “Sommergewitter”, describing “(...) back then our parents came from Turkey with two bags, that’s why I hunt the paper now (...)”. He justifies criminal economic activities as a necessary strategy for survival in Kreuzberg e.g. in “Airberlin” “18 year olds drive (Audi) RS6, 15 year olds pack up drugs” (2023) or “here you deal drugs at 16, where passersby on sidewalks look away at action” (“Ms Jackson”, 2023). For Pashanim as a representative of third-generation migrant youth this neglect has manifested in a distinctive defiance of state and police, evident through the way he moves and acts in the city e.g. running from the police, driving illegally, carrying drugs and weapons in public and lying in court. “Airberlin” (Figure 13) discusses critically German migrant policy, condemning:

“the state doesn’t see us as its protégé/

it sees us as an imported problem/

you could never understand how we feel/ they’d rather never see us here again/

but we built this country up/

and our anger has built up/

(...) I’ll be a voice for us”

He also draws on personal experiences with racial profiling (“not even 16, with knees on the back of my head”), regular apartment searches (“they’re storming the flat without a reason/we just wanted to be safe and healthy” (“Airberlin” 2023), and more generally “drive through our area every multiple times per hour” (“Ms Jackson”, 2023). There is a notable contrast between the deep attachment for Kreuzberg as “his” neighbourhood and this spite for Germany as a state more widely, which demonstrates what Hinze (2013) describes as the “hybrid home”: third-generation immigrants identify more strongly with their locality than with either German or Turkish nation, symbolizing their hybrid transnational identity with elements of both. Validating his local authenticity through postcode references, Pashanim raps “61 Original-Berliner/you’ll always see me around this corner or another one” (Superjung) or “long nights in 61, took my first steps in the area (...) you’ll see me in my Kiez, won’t see me at KaDeWe” (“Sommergewitter”) (iconic department store emblematic of Berlin) (Figure 14- 15).

Figure 15: Public transport map of Kreuzberg in “Ms Jackson” video. Source: Youtube (2023).

Nevertheless, Kreuzberg remains in its position as an important diasporic haven for the Turkish community, a function that is strongly favoured by Berlin’s unique neighbourhood localism. This community is a recurring theme in Pashanim’s texts: In “Airwaves” (2020), he describes “kick-ups with friends and passersby greet us” and in “Sommergewitter” (2021)“and we’re standing on the street, greeting people that we know”. More political in the recent “Japan Trikot” (2023) he says, “we’re standing on corners at night and we’re standing with Gaza”, lyrically bridging the geographical distance between Turkish Kreuzberg and Turks in Palestine. Pashanim’s auto-ethnographic account as a third-generation migrant in Kreuzberg dominated by semi- legal hustling, discrimination, and community bonds represents the potential of rap as a lens for transnational urban identities and the interaction between local housing and national integration policies.

Teuterekordz: Exercising the Right to Prenzlauer Berg

Teuterekordz is a rapper collective from Prenzlauer Berg, at first glance standing out for their hedonistic tales of Berlin’s nightlife, at second glance interweaving them with anti-fascist political messages. As this section will show, their political messaging is fundamentally spatial not just in explicit wording but also against the background of their associated neighbourhood. Named after Teutoburger Square in Prenzlauer Berg, where the group of 6 both grew up and met, the neighbourhood has today become synonymous with gentrification and neoliberalisation of urban policy in Berlin (Figure 16-17) (Papen 2012).

Figure 16: Map of Prenzlauer Berg’s location in Berlin. Source: Wikipedia.

Figure 17: Teuterekordz at Teutoburger Square, Prenzlauer Berg. Source: Helios37 (2022).

A former working class neighbourhood in East Berlin, the area’s extensive 19th-century housing stock deteriorated under GDR neglect in favour of socialist housing estates (Figure 18) (Bernt 2012). With urban renewal strategies after reunification in the 1990s, the area became subject to private developers and rent increases (Bernt 2012). Throughout the last two decades, PrenzlauerBerg’s face has changed drastically, to an upper-middle class family idyll of cafés, boutiques and playgrounds (Figure 19) (Papen 2012). Consequent resident displacement and closure of establishments is a core message in Teuterekordz’ texts, e.g. in “Bundespressekonferenz” (2022): “market prices go up at Frankfurt stock exchange/ but all the money goes to flat rent/ the clubs go bust, the houses are cleared”. Since the 1980s, Prenzlauer Berg has been a niche for artists, students, squatters and the alternative scene, and citizen movements actively opposed displacement in the 1990s, most prominently the coalition “We All Stay” (Bernt&Holm 2009). The area’s tradition of such Lefebvrian right to the city exercises continues within Teuterekordz work, reconfigured in the form of New Wave rap. Teuterekordz have self-proclaimed their “not-rough” upbringing, yet as 90’s kids witnessed significant neighbourhood change first hand. It is this these socio-politically produced urban changes that Teuterekordz draw their emotional momentum from.

Figure 19: Prenzlauer Berg today. Source: Berlin.de (2024).

Figure 18: Old buildings in Prenzlauer Berg mid 1990s. Source: Tip Berlin (2023).

Arguing for lower rents and expropriation of owner-investors by the state, they rap “Going out, immediately have hate in my stomach/street is loud, because demonstration escalates/because some fat cats have sold parts of this city again” (“Beton Steine Scherben”, 2024) and “and they grab my mate without reason on May 1st/One day these houses will be ours again/renters against investors like Padovicz” (“Beton Steine Scherben”, 2024), with May 1st traditionally a day for leftist demonstrations in Berlin, and Gijora Padovicz being an infamous Berlin real estate developer (Figure 20).

Architectural changes serve Teuterekordz as stylistic means by which to illustrate gentrification and displacement by urban policy, for example in “Berlin Syndrom” (2024): “on new buildings windows large, that’s where love is mostly gone” or “where Kaiser’s used to be, now entwining glass facades/you talk about free market, i talk about government failure” (“Bundespressekonferenz”, 2022), criticising the loss of local institutions such as the supermarket Kaiser’s (Figure 21).

Figure 21: New real estate developments in Jablonskistraße, Prenzlauer Berg. Source. Gewobag (2024).

Teuterekordz experience of the built environment and political statements about the perceived deficiencies stem less from hardship and need than from a deep political belief in equitable urban life. While it would be deterministic to insinuate a causal relationship for the members of Teuterekordz here, the parallel between a leftist tradition in formerly East German Prenzlauer Berg and a continuing political legacy of East German socialism and is still noteworthy in this context. Hints at this link to Berlin’s division can be found in “Bundespressekonferenz” (2022): “Fuck you Germany! Lindner idiot/Police and owners successful at evicting/ social Union what hypocrites/West German porch, plate with a gold rim”, condemning liberal Finance Minister Christian Lindner and the conservative Union party, both with West-German backgrounds.

Teuterekordz’ strong-worded Marxist critique thus illustrates New Wave rap as a modern means to assert rights to the city through the stylistic instrumentalization of architectural and demographic neighbourhood change.

CONCLUSION

The analysis of three representatives of German New Wave rap associating themselves with three politically, demographically, and geographically different neighbourhoods has shown that the emergence of a new subgenre is accompanied by more differentiated and multidimensional spatialities than classical Gangsta Rap. More specifically, it has shown how the function of rap is enabled and malleable by its local context, to platform personal expression but also offer political narratives for audience identification. This essay has argued that the different functions New Wave rap can take on are written from and thus to be read through the locality they originate in. For Pashanim, rapping about Kreuzberg offers a way to reconcile his post-migration German-Turkish urban identity amidst socioeconomic precarity and conflicts with the police in the transnational, often medially ghetto-ized third space of the neighbourhood. For BHZ, rapping about Schöneberg is a homage to the carefree youth and tight-knit community their residential middle-class neighbourhood enabled them to have. For Teuterekordz, rapping about Prenzlauer Berg is an exercise of their right to the city, amidst witnessing their neighbourhood turn into a hotspot for gentrification and neoliberalisation. These examples of New Wave represent a break with Gangsta tradition through their more stable social situations, but also through more political stances, a phenomenon that can be approached through the Frankfurt school of critical theory: an absence of revolutionary collectivisation amongst the marginalised due to the all-consuming materialistic pressures of daily struggles for survival, with the time and mindspace to organise being a luxury good for the slightly better off. The contribution of this essay has been not just a qualitative analysis of rap production allowing for reconstructing urban lifeworlds of an increasingly prominent youth subculture but also developing a new empirical approach to the field of urban anthropology.

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1. Map of Schöneberg’s location in Berlin. Source: maps Berlin (2024). (https://maps- berlin.com/maps-berlin-districts/schoeneberg-berlin-map)

Figure 2. Schöneberg Street. (https://www.berlin.de/en/districts/schoeneberg/)

Figure 3. BHZ at Apostel-Paulus Church. Source: Juice (2019). (https://juice.de/bhz-feature-2/)

Figure 4. BHZ on bench. Source: Youtube (2021). (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8JcA6sjQgzQ)

Figure 5. BHZ at cornershop. Source: Youtube (2021). (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8JcA6sjQgzQ)

Figure 6. BHZ at Rüyam’s. Source: Youtube (2021). (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8JcA6sjQgzQ)

Figure 7. BHZ at Tina’s. Source: Youtube (2021). (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8JcA6sjQgzQ)

Figure 8. BHZ on underground. Source: Youtube (2020). (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OG_IjNjMR3Y)

Figure 9. Map of Kreuzberg’s location in Berlin. Source: Institute for European History (2004). (https://ghdi.ghi-dc.org/map.cfm?map_id=329)

Figure 10. Turkish Shops in Kreuzberg 1983. Source: German Information Centre (2024). (https://ghdi.ghi-dc.org/sub_image.cfm?image_id=2378)

Figure 11. Kreuzberg Merkezi. Source: Wikipedia (2024). (https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Kreuzberg_Merkezi,_Berlin.jpg)

Figure 12. Transnational Symbolism in “Ms Jackson”. Source: Youtube (2023). (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J5-rJsiKJng)

Figure 13. Aerial shot of Kreuzberg in “Airberlin”. Source: Youtube (2023). (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TcTtp-tb7Xs)

Figure 14. Local Baklava Bakery in Kreuzberg in “Sommergewitter”. Source: Youtube (2021). (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YOWEsoigyPg)

Figure 15. Public Transport Map of Kreuzberg in “Ms Jackson”. Source: Youtube (2023). (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J5-rJsiKJng)

Figure 16. Map of Prenzlauer Berg’s location in Berlin. Source: Wikipedia (2024). (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Prenzlauer_Berg.png)

Figure 17. Teuterekordz at Teutoburger Square. Source: Helios37 (2022). (https://www.helios37.de/event-details/teuterekordz-verlegt-ins-luxor)

Figure 18. Prenzlauer Berg in the 1990s. Source: Tip Berlin (2023). (https://www.tip- berlin.de/stadtleben/geschichte/prenzlauer-berg-1990er-jahre/)

Figure 19. Prenzlauer Berg today. Source: Berlin.de (2024). (https://www.berlin.de/en/districts/prenzlauer-berg/920610-6361316-trendy-neighborhoods-in- the-south.en.html)

Figure 20. Activists with banner in “Beton Steine Scherben”. Source: Youtube (2024). (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PhDyoQIcaaU)

Figure 21. New real estate developments in Prenzlauer Berg. Source: Gewobag (2024). (https://www.gewobag.de/bauen-in-berlin/bauprojekte/jablonskistrasse-12-in-berlin- prenzlauer-berg/)

References

Appadurai, A. (2003). The production of locality. In Counterworks (pp. 208-229). Routledge.

Auge, Y., Ringel, F., & Fleischmann, L. (2023). Deutschrap als innovatives Instrument des Regionalmarketings? Die Vermarktung geographischer Imaginationen Ostdeutschlands in

Rapmusik. Standort, 47(2), 113-119.

Barth, J., & Barth, S. (2022). Wir lungern auf Straße, aber wir sind keine Gangster. In Deutscher Gangsta-Rap III. Soziale Konflikte und kulturelle Repräsentationen (Vol. 56).

Barwick, C., & Beaman, J. (2019). Living for the neighbourhood: marginalization and belonging for the second-generation in Berlin and Paris. Comparative Migration Studies, 7, 1-17.

Beadle, J. J. (1993). Will pop eat itself?. (No Title).

BHZ (2016). Hoodparadies. Berlin: Sony Music. BHZ (2021). Hoodnights. Berlin: Sony Music. BHZ (2020). Regen Prasselt. Berlin: Sony Music. BHZ (2021). Church. Berlin: Sony Music.

Buß, C. (2002). Rap op der Eck-Rap in Köln: Regionale Bezüge einer urbanen Poesie.

Bennett, A. (1999). Hip hop am Main: the localization of rap music and hip hop culture. Media, Culture & Society, 21(1), 77-91.

Bernt, M. (2012). The ‘double movements’ of neighbourhood change: Gentrification and public policy in Harlem and Prenzlauer Berg. Urban Studies, 49(14), 3045-3062.

Bernt, M., & Holm, A. (2009). Is it, or is not? The conceptualisation of gentrification and displacement and its political implications in the case of Berlin‐Prenzlauer Berg. City, 13(2-3), 312-324.

Bock, K., Meier, S., & Süß, G. (2007). HipHop meets Academia: globale Spuren eines lokalen Kulturphänomens (p. 332). transcript Verlag.

Dell, A. C. (2021). The Turkish-German Bridge: A Unique Socio-Spatial Construction in Kreuzberg. Turkish Journal of Diaspora Studies, 1(2), 19-36.

Dietrich, M., & Seeliger, M. (Eds.). (2012). Deutscher Gangsta-Rap: Sozial-und kulturwissenschaftliche Beiträge zu einem Pop-Phänomen. transcript Verlag.

Dietrich, M., & Seeliger, M. (Eds.). (2022). Deutscher Gangsta-Rap III: Soziale Konflikte und kulturelle Repräsentationen (Vol. 56). transcript Verlag.

Dumanlı, Ö. (2021). The Relationship Between the Police and Third Generation Turkish Immigrants in Germany. Turkish Journal of Diaspora Studies, 1(2), 37-55.

Forman, M. (2002). The'hood comes first: Race, space, and place in rap and hip-hop. Wesleyan University Press.

Güney, S., & Kabaş, B. (2017). Migrant spaces and childhood: Growing up in Kreuzberg. Urbana, 18, 1-23. Güngör, M., & Loh, H. (2017). Vom Gastarbeiter zum Gangsta-Rapper?. Diversität in der Sozialen Arbeit, 68. IEG-MAPS, Institute of European History, Mainz / © A. Kunz, 2004 Ion Miles and Monk (2019). 3062. Berlin: Sony Music

Güney, S. (2017). The Existential Struggle of Second-Generation Turkish Immigrants in Kreuzberg: Answering Spatiotemporal Change. Space and Culture, 20 (1), 42-55.

Holm, A. (2006). Urban renewal and the end of social housing: The roll out of neoliberalism in East Berlin's Prenzlauer Berg. Social Justice, 33(3 (105), 114-128.

Hulleman, J. B. (2017). Contesting Neoliberal Urbanism-Comparing processes of protests in de Jordaan, Prenzlauer Berg and Harlem (Master's thesis).

Kahraman, Z. E. (2014). Integration strategies of Turkish immigrants living in Kreuzberg, Berlin. Migration- global processes caught in national answers, 54-78.

Kaya, V. (2021). “Rap muss Cool Sein”: Deutschtürkische Rapper in der Deutschen HipHop-Kultur. IstanbulBerlin. https://www.istanbulberlin.com/en-de/verda-kaya-hip-hop/

Kemp, A., Lebuhn, H., & Rattner, G. (2015). Between neoliberal governance and the right to the city: Participatory politics in Berlin and Tel Aviv. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(4), 704-725.

Krämer, J. (2021). Berlin Calling: Wie die New Wave Deutschraps Wichtigstes Movement wurde. HipHop.de, 10 April. https://hiphop.de/magazin/meinung/berlin-new-wave-deutschrap-bhz-pashanim

Lang, B. (1994). Mythos Kreuzberg. Leviathan, 22(4), 498-519.

Lefebvre, H. (2014). The Production of Space (1991). In The People, Place, and Space Reader (pp. 289–293). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315816852

Munderloh, M. K. (2017). Rap in Germany–multicultural narratives of the Berlin republic. German pop music: A companion, 189-210.

Özüekren, S., & Ergoz-Karahan, E. (2010). Housing Experiences of Turkish (Im)migrants in Berlin and Istanbul: Internal Differentiation and Segregation. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36(2), 355–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830903387477

Pashanim, AXL Beats and Stickle (2023). AIrberlin. Berlin: Urban Records.

Pashanim, Ambezza, KANE13, Stickle (2023). Draußen essen spat schlafen. Berlin: Urban Records Pashanim, SIRA, southstar, Sebo (2023). Ms Jackson. Berlin: Urban Records.

Pashanim and Mistersir (2023). Superjung. Berlin: Urban Records.

Pashanim and Stickle (2021). Sommergewitter. Berlin: Urban Records.

Pashanim and Stickle (2020). Airwaves. Berlin: Urban Records.

Pashanim Benihana Boy, Vico61, Ezco44 (2020). Laufe auf der Straße. Berlin: Urban Records.

Papen, U. (2012). Commercial discourses, gentrification and citizens’ protest: The linguistic landscape of Prenzlauer Berg, Berlin 1. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 16(1), 56-80.

PULS Musikanalyse (2020). Pashanim: Wie er Straßenrap und Arthouse verbindet. (Video). Youtube.

Pashanim: Wie er Straßenrap und Arthouse verbindet II PULS Musik Analyse - YouTube.

PULS Musikanalyse (2022). Pashanim: Wie lange trägt ihn der Hype noch? (Video). Youtube.

Pashanim: Wie lange trägt ihn der Hype noch? || PULS Musikanalyse (youtube.com).

PULS Musikanalyse (2022). Pashanim: Wie “Himmel über Berlin” auf Kritik eingeht. (Video). Youtube. Pashanim: Wie “Himmel über Berlin” auf Kritik eingeht || PULS Musikanalyse - YouTube.

Rodel, L. Vernacular Politics and Neighbourhood Nationalism in London’s Drill Scene. Anthropology of Architecture. https://www.anthropologyofarchitecture.com/vernacular-politics-drill

Scharenberg, Albert (2001): Der diskursive Aufstand der schwarzen ›Unterklassen‹. HipHop als Protest gegen materielle und symbolische Gewalt. In: Weiß, Anja et al. (Hg.): Klasse und Klassifikation. Die symbolische Dimension sozialer Ungleichheit. Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag. S. 243- 269

Schicht, G. (2013). Racial Profiling bei der Polizei in Deutschland. Bildungsbedarf? Beratungsresistenz?. ZEP: Zeitschrift für internationale Bildungsforschung und Entwicklungspädagogik, 36(2), 32-37.

Seeliger, M., & Dietrich, M. (Eds.). (2017). Deutscher Gangsta-Rap II: Popkultur als Kampf um Anerkennung und Integration (Vol. 50). transcript Verlag.

Seeliger, M. (2016). Deutschsprachiger Rap und Politik. Rap im, 21, 93-109. SIRA and Ion Miles (2022). Powerade. Berlin: Sony Music

Soysal, L. (2004). Rap, hiphop, Kreuzberg: Scripts of/for migrant youth culture in the WorldCity Berlin. New German Critique, (92), 62-81.

Stehle, M. (2017). Narrating the ghetto, narrating Europe: From Berlin, Kreuzberg to the banlieues of Paris. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture, 3(3).

Uschmann, O., & Kleiner, M. S. (2022). Rückenprobleme: Die Narrative der Straße und ihre Krise im deutschsprachigen Gangsta-Rap. In HipHop im 21. Jahrhundert: Medialität, Tradierung, Gesellschaftskritik und Bildungsaspekte einer (Jugend-) Kultur (pp. 25-57). Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

Vu, A. T. (2021). Understanding German-Turkish Identity in the Context of Deutschrap.