Autoconstrucción: Collaborative self-construction in Colonia Ajusco

This paper explores how self-construction practices in Mexico City’s Colonia Ajusco embody a collaborative processual relationship between residents and the built environment. From Mexican artist Abraham Cruzvillegas’s artistic practice, I take his concept of autoconstrucción and his autobiographical work as an ethnographic resource. Where self-construction takes place at the level of the community and neighbourhood, infrastructure is bolstered by warm systems of persons. At the level of the individual house, persons and houses transform alongside each other, made visible in the house’s appearance and materiality. Ultimately, I suggest Ajusco is continually made through a dynamic interplay of social, material and built worlds.

Mexican artist Abraham Cruzvillegas’s artistic practice is deeply rooted in the built environment of his hometown in Mexico City (fig 1). This essay takes his autobiographical work and his concept of autoconstrucción as an ethnographic resource to explore how self-construction practices in the Colonias Populares of Mexico, namely Colonia Ajusco, embody a collaborative processual relationship between residents and the built environment. I focus on how persons and houses collaboratively make and shape each other in a process of mutual ‘self-construction’.

To foreground my discussion, I provide historical background on Ajusco’s formation and contextualise self-construction as a practice of necessity within conditions of socio-economic insecurity. I address how Colonia Populares can be mis-portrayed under the notion of urban informal settlements to make the case for an ethnographic approach. Focusing attention on ground-level processes, I explore how self-construction occurs 1) at the level of the community and neighbourhood, where collectively building houses fosters relations between residents, while residents in turn bolster urban operations to support the district’s growth; and 2) at the level of the individual house, where persons and houses transform alongside each other, made visible in the house’s appearance and materiality.

Figure 1. Abraham Cruzvillegas, Installation view of “The Autoconstruccion Suites”, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

Abraham Cruzvillegas and the spirit of Autoconstrucción

“Autoconstrucción: a definitively unfinished inefficient unstable affective emotional delirious joyful affirmative sweaty fragmentary empiric weak happy contradictory solitary indecent sensual amorphous warm and committed index.” –– Abraham Cruzvillegas (Carlos, 2013)

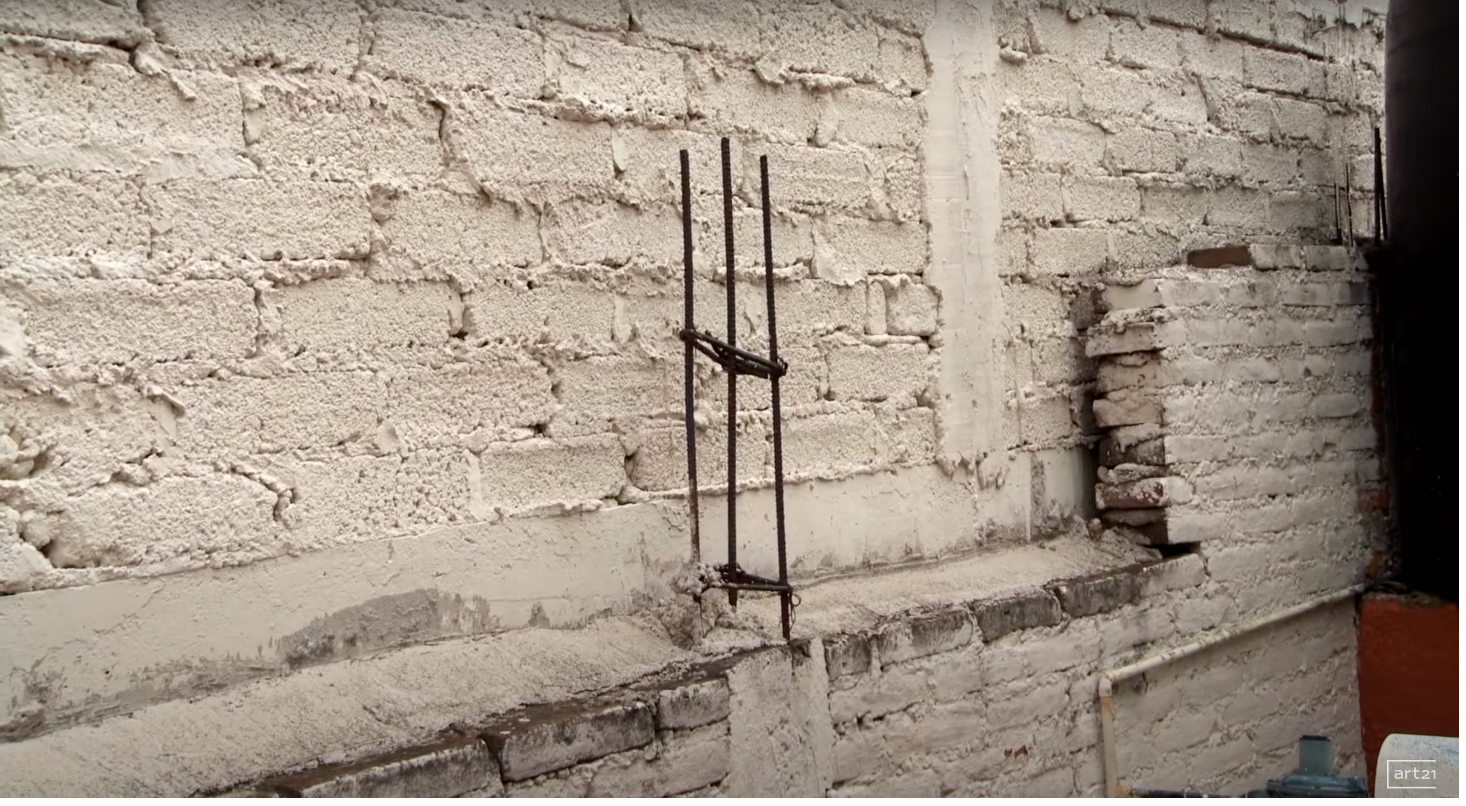

This is the definition one finds for the term autoconstrucción in artist Abraham Cruzvillegas’ text of ‘personal definitions’: the word broken into a messy, miscellaneous, paradoxical collection of descriptors. Autoconstrucción lies at the heart of his art practice and is rooted in the urban landscape of his childhood. The term, literally meaning self-construction, draws on the improvisational construction methods and techniques of Ajusco (fig 2). Ajusco is one of many districts, or Colonia Populares, in Mexico City formed by rural populations taking on the responsibility for house construction as resident-builders. For the first 20 years of his life, Cruzvillegas observed and helped shape the gradual construction of his parents’ house and of his neighbourhood.

Figure 2. Cityscape of Ajusco, still from Autoconstrucción: The Film (Cruzvillegas, 2009).

Cruzvillegas’ concept of autoconstrucción serves as a way to engage with how Ajusco’s residents themselves make sense of self-construction; I regard his personal history and autobiographical writing as a rich ethnographic resource. Across his multidisciplinary oeuvre featuring song, theatre, film, writing and sculpture, self-building practices form the basis of Cruzvillegas’ thinking and methodology. He emphasises that his work does not seek to represent self-build housing; rather, he seeks to “activate the dynamics of autoconstrucción” (Tateshots, 2015). In other words, he expresses the ethos of self-construction through an artistic practice in which materials are found and recovered from local sites, then transformed through methods of making that are improvisational. His works are definitively unfinished, unfixed, aesthetically unstable assemblages that often involve collaborations with the surrounding community and environment (Dante, 2013). Further, autoconstrucción serves as a metaphor for the articulation of self-identity (Kim, 2013): it is the practice of building houses, but also simultaneously the practice of building community and building the self. Throughout this essay, I will illustrate how this plays out in Ajusco. To follow, I set the scene and provide background on the Colonia’s formation.

Becoming Colonia Ajusco

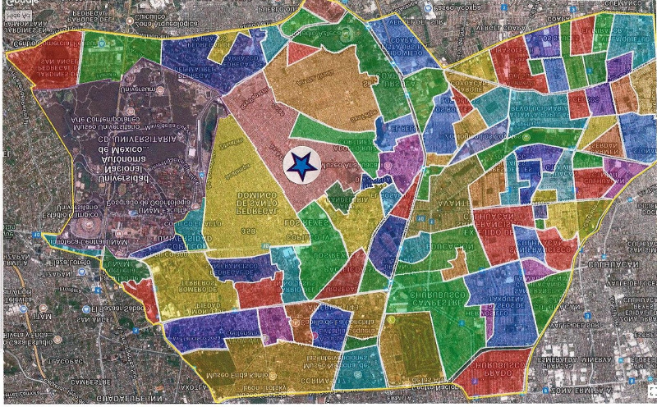

Colonia Ajusco is located in the volcanic area of Pedregales de Coyoacán at the Southern edge of Mexico City (Fig 3, 4). It is one of numerous informal settlements that constitute the city’s urban fabric. From the 1950s, rural exodus towards Mexico’s urban centre resulted in hundreds of new, unplanned districts erupting around the city’s periphery. Construction on Ajusco began in the 1960s by migrants who invaded and occupied the unused land; Cruzvillegas’ family were amongst the early settlers. The term invaded consciously denotes the illegal nature of urbanization at the time of establishment that characterise informal settlements (Valette, 2018). It is necessary to acknowledge that Colonia Populares ensue from and are a part of struggles over land and housing.

The second half of the 20th century was a period of dramatic urbanisation in Mexico, driven by rapid industrialisation and intra-city migration (Ward, 1976). The promise of post-WWII modernity drew rural migrants towards the urban centre in search of work opportunities and improved livelihoods (Alix-Garcia, 2018). But as Cruzvillegas describes his and his community’s experience, “there was no real Modern [economic] moment in Mexico” and for many “the promise came along with the failure of the promise itself” (New Museum, 2011). Thus, self-constructed neighbourhoods are not an isolated or accidental phenomenon, but a direct response to a population’s circumstances of social and economic insecurity. Research in Latin American cities have shown that housing programs for low-income urban populations are often devised by the state as an afterthought to industrialisation and development projects (see Ward, 1990; Peattie 1987; Holston 1989). Residents of informal colonias have developed political strategies regarding land tenure disputes and land rights (Barriga, 1995); for instance, in the Coyoacán de Pedregales, residents organised occupations of land when faced with evictions on the pretext that there were no land titles (Cruzvillegas, 2008: 32). Importantly, anthropological work has been done on the role of the state and individuals in issues of secure housing (see Alexander et al. 2018). However, within the scope of this essay I do not expand upon this further, instead shifting focus towards the self-construction processes that make the Colonia. Continuing, I contextualise my exploration of self-construction practices in terms of how it speaks to wider discourse on urban informal settlements.

(Discursive Marginalisation of) Urban Informal Settlements

Prominent discourses in urban development and debates have tended to frame urban informal settlements in oversimplified terms to which, as I subsequently demonstrate, Cruzvillegas’s autobiographical accounts of Ajusco provide a different and more granular perspective.

Colonia Populares or urban informal settlements account for a significant proportion of housing in many cities in Latin America and the global South (Lombard, 2014: 1). Such settlements are typically defined by criteria such as self-build housing, low level of existing services and infrastructure, irregular land tenure, and residents with low-incomes (Lombard, 2014: 3). These components are associated with poverty, irregularity, and marginalisation. Urban informal settlements are often framed as manifestations of urban crises and a problem to be solved. For instance, a 2006 UN-Habitat report on world cities describes informal settlements as 'a manifestation of poor housing standards, lack of basic services and denial of human rights, [but] also a symptom of dysfunctional urban societies where inequalities are not only tolerated but allowed to fester.' " (UN-Habitat in Lombard, 2014: 3). While these accounts are often motivated by social justice and stem from a concern with the existing inequalities such settlements point to, Melanie Lombard suggests that conceptualisations of informal settlements contain generalising assumptions and require rethinking (Lombard, 2014).

For one, there is a persistent portrayal of informal settlements in exceedingly negative or sensationalised terms – what Ananya Roy describes as “apocalyptic and dystopian narratives of the slum” (Roy 2011: 224). Slum as a “metonym” for underdeveloped urban areas in cities has resulted in their portrayal as simultaneously abject and uplifting, both crisis and heroism (Roy, 2011: 224). Further exacerbating flattened understandings of informal settlements is the dualistic framing of informality and formality, which obscures how informal and formal sectors are entangled in any urban space (Lombard, 2014: 10). As Castillo has pointed out, and as Wissel has shown in his ethnographic comparison of Colonia Antorcha and Sierra Hermosa (districts of ‘informal’ and ‘formal’ registers respectively), informal and formal settlements exist along a fluid spectrum across which the two move towards each other in a process of counter-directional development (Wissel, 2019: 119). Informal housing gradually meets formal standards as land ownership is regularised and as the state, private sector or the work of resident-builders bring formal urban infrastructure, equipment, and services into the district (Castillo in Wissel, 2019: 119). I illustrate this later in the case of Ajusco. Meanwhile, formal settlements take on informal qualities as ready-to-use buildings are transformed, expanded, and adapted by inhabitants (Wissel, 2019: 119).

Significantly, discourses are implicated in the construction of marginalisation. When language, image, and stories are projected as ‘reality’, a certain ideological construction of a place and people is created. As Lombard suggests, they are often founded on gaps in understanding, the exclusion of certain perspectives and negative interpretations (Lombard, 2014: 3). Such discourses have the capacity to produce marginalisation, to real effects of stigmatisation, discrimination, eviction, and displacement (Lombard, 2014: 4). In the case of informal urban settlements in Mexico, their portrayal as unplanned and disorderly can be used as a pretext to justify redevelopment, and residents and housing stereotyped as illegitimate and inadequate (Lombard, 2014: 4). This can disregard the productive spaces of informality and agency of informal urban dwellers (Lombard, 2014: 4). Lombard argues that flattened understandings of urban informal settlements are due in part to a lack of understanding of the vernacular processes that make these places (Lombard, 2014: 3). She points to the merit of ethnographic approaches to hone in on such processes and nuance the understanding of how residents meaningfully and intentionally inhabit their built environment (Lombard, 2014: 6-7). Following Lombard, I examine how Cruzvillegas’ accounts of self-construction relate residents to their built environment in processes of collaborative making. To continue, I unpack how self-construction takes place at the level of the community and neighbourhood.

‘People as Infrastructure’ and warm systems

In Ajusco, the community and the built environment of the neighbourhood mutually shape and form each other. To borrow a phrase from AbdouMaliq Simone, “People work on things to work on each other, as these things work on them” (2004: 376). As residents collectively build houses and self-organise to secure provisions, community relations and neighbourhood operations are formed simultaneously.

In the absence of external services, resources, planning, and funds, residents of Ajusco fill the gaps in housing and infrastructural provision with resources at hand in improvisational methods of making do (Wissel, 2019). Here I draw upon Simone’s concept of “people as infrastructure”. Infrastructures are conceptually difficult to define. In their broadest sense, they are “matter that enable the movement of other matter… built networks that facilitate the flow of goods, people or ideas and allow for their exchange over space” (Larkin, 2013: 328-329). Most often, when understood in material terms they are “reticulated systems of highways, pipes, wires, or cables” (Simone, 2008: 407). But as Larkin traces in The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure, there is a diversity of ways to conceive of and analyse infrastructures as variably technological, biological, social, and financial systems. Simone’s anthropological work expands the notion of infrastructure to the activities of people. Residents of limited means or who inhabit spheres of uncertainty employ themselves as the resource by which to “reach and extend across a larger world and enact possibilities of urban becoming” (Simone in Wissel, 2019: 35). Persons form intersections by engaging “combinations of objects, spaces, persons and practices” that make expanded spaces of economic and cultural operation available (Simone, 2008: 407)

This resonates in Ajusco, where production and development of housing and the neighbourhood facilities is social in character and relies on collective effort, active participation, and the affective and physical presence of residents. To fulfil housing and infrastructural needs, residents source and bring together the materials available in the environment and the bodies, skills, and knowledge of members of the community. Here I present another key term in Cruzvillegas’s autoconstrucción:

"Warm: a warm system means an organic organization of re-arrangeable elements, in which subjectivity, affection, emotion, but mostly needs, rule." (Carlos, 2013)

Cruzvillegas conceives of self-building as a “process full of warmth”, founded on the collaboration and solidarity of neighbours and relatives in response to precarious conditions. In his autobiographical work Autoconstrucción (2008), Cruzvillegas remembers neighbours with familiarity, mapping out the street of his house by names, livelihoods, families, and anecdotes. To the left of the Cruzvillegas house were cabinet maker and shopkeeper Don Juan Alvarez, his father’s cousin, and her husband and nine children (Cruzvillegas, 2008: 58). To the right were retired bureaucrat and amateur artist Don Zénon Moreana, opposite to Doña Micaela Retiz, who would give the residents injections when they fell ill (Cruzvillegas, 2008: 56). They were amongst the people who, alongside Cruzvillegas’s family, built his house like a “slow sculpture” in a process of “raising, demolishing, assembling and undoing” (Cruzvillegas, 2008: 5). His recounts of periods of construction work describe the festive atmosphere and character of self-building:

“Every weekend there was a festive air around the dusty activities of moving chalk, cement and sand; the women would cook and help to carry water, haul stones, bricks, bags of cement, buckets of sand or fizzy drinks, under a burning sun, in a challenging atmosphere moved by a spirit of busy and efficient collectivity.” (Cruzvillegas 2008: 18)

As residents build, they also share food, drink, stories, and time; as the neighbourhood is realised materially, it is also realised socially and infrastructurally. Cruzvillegas recalls afternoons where men and women would collectively stir cement to the rhythm of cumbias and ranchera ballads (2008: 18). Residents offer their affective presence to “generate the ambient environment of everyday life” (Larkin 328). Their physical bodies move and reconfigure matter, as they “carry water”, “haul stones”, and “stir cement” (Cruzvillegas 2008: 18). In a self-organised division of labour, residents provided each other with services, like Doña Micaela Retiz as the neighbourhood nurse. In the early stages of Ajusco’s development, when neighbourhood provisions were limited, persons naturally monopolized services. For instance, for years Casa Real was the only shop that provided all building materials. At times this monopoly produced conflict and tension, as when the drinking water tap of the area was coincidentally situated in front of a resident’s home; consequently, the household became the ‘owners’ of the water (Cruzvillegas: 2008: 20). Until houses were equipped with showers and piped water later in the district’s development, residents had to go to the owner of the water to retrieve it (Cruzvillegas, 2008: 60). Throughout the neighbourhood there were resident-owners of light, of a telegraph pole, of a street (Cruzvillegas, 2008: 20). As Cruzvillegas describes, “the relations between people, inside and outside the houses, transform spaces” (Cruzvillegas, 2008: 56). In ‘warm systems’ of individuals organically and ‘re-arrangeably’ organised, residents actively negotiate how the neighbourhood is used and developed.

The growth of the La Bola market (fig 5), from an improvised structure made with sheets of cardboard and tar paper to the geodesic dome that gives it its name, is evidence of the constructive conjunctions of residents that expanded Ajusco’s access to external services and resources (Simone, 2004: 407). Mercado de la Bola is the epicentre of the district as the area’s first commercial centre, a site of political demonstration and public events, and a meeting point for community discussions and exchanges around shared problems (Cruzvillegas, 2008: 45). Cruzvillegas’s mother, Maria de los Angeles Fuentes, co-founded the market together with an early traders’ organisation to serve as the district’s principal source of food, clothing, and articles of primary need (Cruzvillegas, 2008: 45). As Cruzvillegas attests, what made its formal construction financed by the city government possible was “the magnitude of the needs which shaped it” (Cruzvillegas, 2008: 45). La Bola affirms the fluidity between formality and informality, as an instance where ‘informal’ networks of persons, materials and practices effectively bring in and converge with ‘formal’ institutions. Amongst many others, Maria became an intermediary between the community street sellers and politicians and bureaucrats in the process of La Bola’s formalisation.

Figure 5. Mercado de La Bola in Ajusco, photograph in Autoconsstrucción (Cruzvillegas, 2008)

As I have shown, self-construction takes place at the level of the neighbourhood in that the social workings of the community, the district’s urban facilities and operations, and the physical construction of buildings unfold and take shape in conjunction. In the following section, I turn my attention to how self-construction plays out at the level of the individual house, where residents and their houses grow alongside each other.

Toothpaste Bricks and Rebar

The façade and materiality of Ajusco’s houses visibly attest to the way in which the construction and transformation of houses parallels the growth of persons. Examining residents and their homes emphasises how self-build practices engage with materials, houses, and persons as collaboratively and continuously in the making. As a result, the future as a self-made prospect is embodied in the house (Wissel, 2019: 134).

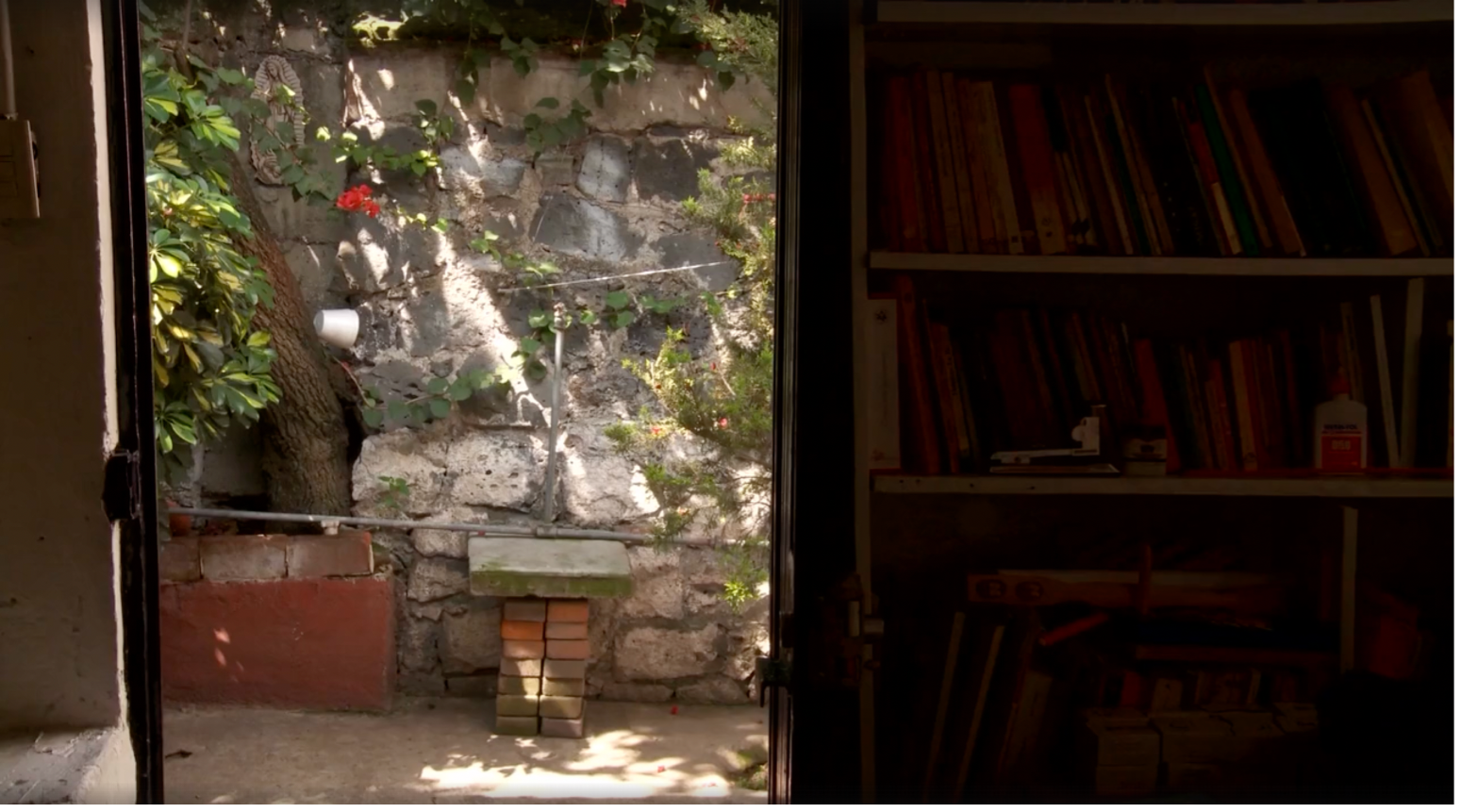

In relation to his artwork, Cruzvillegas describes how he uses “dead things or materials” and “[gives] them a new use by revealing instead of hiding their nature” (Dante, 2013). This reflects the attitude of Ajusco’s residents towards materials in self-building processes. The landscape of Ajusco in the 1960s upon Rogelio Cruzvillegas’ (Abraham’s father) arrival was a “lunar crater… wholly barren and consisting mainly of lava” (Cruzvillegas, 2008: 12). On the empty and notoriously inhospitable terrain, early settlers first began to construct their houses from the volcanic rock that composed the land. Materials were sourced wherever available, often from surrounding neighbourhoods where they had been discarded, to be repurposed by residents into housing structures (New Museum, 2011). That cast-off materials take on new roles echoes Ingold’s assertion that “materials carry on, undergoing modulations as they do so” (Ingold, 2012: 435). This accounts for the houses’ composite materiality. The facades of Ajusco’s houses are aesthetically unpredictable, patchwork assemblages of forms and materials. At one house, black metal doors and windows are framed by walls of undressed brick and unpainted cement, built atop and around walls of original stone from Ajusco’s terrain (fig 6). Elsewhere is an irregularly shaped house whose walls are painted a vivid blue, save for a stretch of white tile (fig 7).

In his text, How Buildings Learn, Stewart Brand states that “the whole idea of architecture is permanence… but it is an illusion” (1997: 2). Self-constructed housing reveals the kink between the idea of architecture and the reality of buildings, as Cruzvillegas suggests when he writes that “the house had always been a mixture of concrete needs and forms that refer to the strange notion of ‘architecture’ ” (Cruzvillegas, 2008: 71). Self-constructed houses are the fluid fact to the crystalline idea (Brand, 1997: 2). Examining them shifts thinking from buildings as inert to building as an activity, or from noun to verb (Ingold, 2015: 47). The incrementally built house responds to residents’ specific needs and priorities (McKee, 2008: 2). As such, they are “faithful portraits of their inhabitants” (Cruzvillegas, 2008: 44). Like layers of sediment, the outcropping of structures and composites of material and colour track the passing of residents’ lives. Thus, details that seem accidental and chaotic contain the logic of residents’ demands and desires. What appears unplanned and disorderly in fact adheres to residents’ prospects for day-to-day life. As Cruzvillegas expresses:

“The formal configuration of the house is first rooted in intuition, in the instinct for survival and the distant reference to what a decent life means, that is satisfying all vital needs, including the visual character of the day-to-day environment, its objects, its ornaments, and the physical relationship with things – ergonomics straight from the heart.” (Cruzvillegas, 2008: 45)

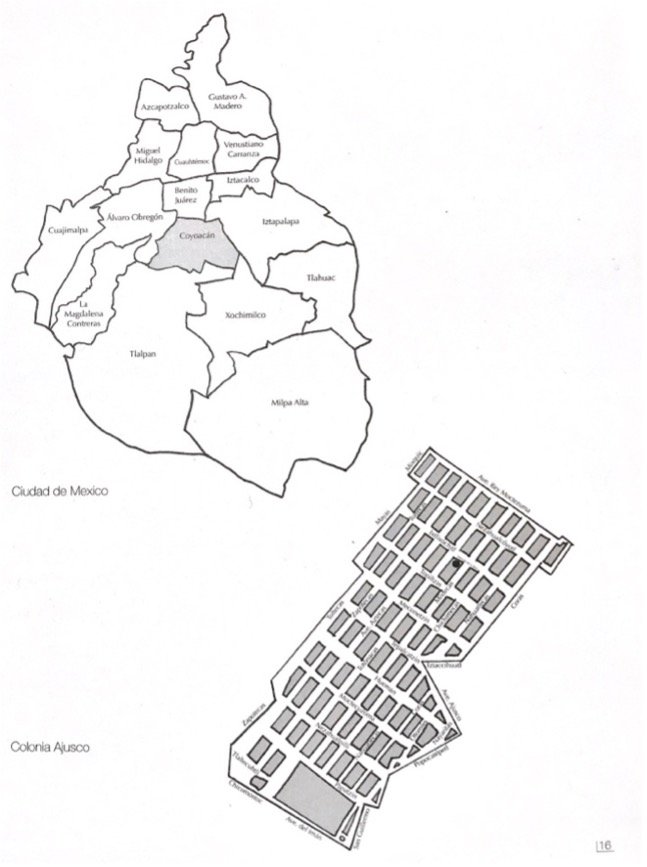

In constant expansions, modifications, and renovations, the house and its occupants mould to each other (Brand, 1997: 7). For instance, banisters designed by a friend were installed throughout the Cruzvillegas house to provide extra support on account of Rogelio’s congenital muscular conditions. After a car accident that meant Rogelio would require a wheelchair, the family installed ramps and adapted corridors and interior spaces to fit the chair (fig 8). As he walks around his family house, Cruzvillegas stops besides a water tap, of which the pipes run against the garden wall, protruding from a precarious table of stone balanced on bricks (fig 9). He points out that this is where his father used to brush his teeth, with a small tub under the tap as a sink. He would spit towards the tree besides him, staining the brick in white over the years like a “slow painting” of his daily routine (fig 10). The building accumulates a record of intimacy.

No house is ever definitively finished but grows and transforms alongside occupants’ continuing life trajectories (Wissel, 2019: 118). Rebar – the reinforcing steel used as rods in concrete – protrude from the tops of buildings in the spirit of possibility, a perpetual reminder of potential growth (fig 11). They rise from roofs in anticipation of “future needs, future generations, future terraces, floors, balconies and extensions.” (Cruzvillegas, 2008: 8).

In close resonance with Tim Ingold’s ecology of materials, persons, materials, and houses in Ajusco are mutable and unfixed, embroiled in form-making processes (Ingold, 2012: 427). Self-construction practically enrols Ingold’s proposal to think of making as a process of ontogenesis in a world of materials and persons that are always ‘becoming’ (Ingold, 2015: 47). Without being informed by architectural expertise or knowledge, self-constructed housing is not realised as the “crystallisation of a design concept” but combines needs, improvisation, intuition, and materials in confluence. Resident-builders produce through “a process of correspondence: the drawing out or bringing forth of potentials immanent” in materials with the capacity to transform (Ingold, 2012). What Cruzvillegas likes about the constructions is how, as he phrases it, “the houses and the people… all overlap together… the activities and the energy, you can see through them. They are transparent.” (Sollins and Dowling, 2014). Throughout the process, persons, materials, and houses participate in the “flow of materials” and in stabilising moments are a temporary stoppage in the “formative history” of life (Ingold in Wissel, 2019: 120).

Conclusion

Against flattened portrayals of urban informal settlements, I have sought to provide granular accounts of the ground-level processes of how such places are made from residents’ perspectives, using Colonia Ajusco and Abrahama Cruzvillegas as a case study. In doing so, I have shown that Ajusco is in a process of continually being made through a dynamic interplay of social, material and built worlds that form and shape each other in conjunction. Neighbourhoods are bolstered by warm systems of persons; residents fill gaps in infrastructural and housing provision, and in the process form social and material worlds. Houses are built through a correspondence between residents and materials and embody prospects for the everyday and future. Buildings, communities, and self-identity are each and collaboratively engaged in a process of making. Returning to Cruzvillegas’s definition of autoconstrucción at the beginning of this essay, I have hoped to shed light on the unfinished, unstable, affective, fragmentary, contradictory, amorphous, and warm nature of Ajusco’s self-construction.

IMAGES

Fig 1. Cruzvillegas, Abraham. “The Autoconstrucción Suites,” Installation, 2014, Walker Art Centre, Minneapolis, by Olga A. Ivanova, Walker Art Center.

Fig 2. Cruzvillegas, Abraham. 2009. Autoconstrucción: The Film. Film. Ajusco, Mexico.

Fig 3. Brundage, Reed. 2017. "New Villages - Old Traditions | Coyoacán: Colonia Ajusco, The Lord Of Miracles And Religión Popular". Mexicocityperambulations.Blogspot.Com.

Fig 4, 5, 6, 7. Cruzvillegas, Abraham. 2008. Autoconstrucción. Glasgow: CCA: The Centre for Contemporary Arts.

Fig 8, 9, 10, 11. Sollins, Susan, and Susan Dowling. 2014. Legacy. Video. United States: Art in the Twenty-First Century.

REFERENCES

TateShots. 2015. Abraham Cruzvillegas – Empty Lot. Video. United Kingdom: TateShots.

Alix-Garcia, Jennifer, and Emily A. Sellars. 2020. "Locational Fundamentals, Trade, And The Changing Urban Landscape Of Mexico". Journal Of Urban Economics 116: 103213. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2019.103213.

Brundage, Reed. 2017. "New Villages - Old Traditions | Coyoacán: Colonia Ajusco, The Lord Of Miracles And Religión Popular". Mexicocityperambulations.Blogspot.Com.

Brand, Stewart. How Buildings Learn : What Happens after They're Built / Stewart Brand. Rev. ed. ed. London: London : Phoenix Illustrated, 1997.

Carlos, Dante. 2013. "A Warm System—The Autoconstrucción Suites". Walkerart.Org. https://walkerart.org/magazine/a-warm-system-the-autoconstruccion-suites.

Castillo, José. 2007. ‘After the Explosion’. In The Endless City: The Urban Age Project by the London School of Economics and Deutsche Bank’s Alfred Herrhausen Society, edited by Richard Burdett and Deyan Sud- jic, 174–85. London: Phaidon.

Cruzvillegas, Abraham. 2008. Autoconstrucción. Glasgow: CCA: The Centre for Contemporary Arts.

Cruzvillegas, Abraham. 2009. Autoconstrucción: The Film. Film. Ajusco, Mexico.

Ingold, Tim. "Toward an Ecology of Materials." Annual review of anthropology 41, no. 1 (2012): 427-42. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-081309-145920.

Kim, Clara. 2013. "Abraham Cruzvillegas: The Autoconstrucción Suites". Walkerart.Org.https://walkerart.org/calendar/2013/abraham-cruzvillegas-autoconstruccion-suites.

Lombard, 2014, Melanie. "Constructing Ordinary Places: Place-Making in Urban Informal Settlements in Mexico." PROG PLANN 94 (2014): 1-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2013.05.003.

McKee, Francis. 2008. "Mutable & Mutual". In Autoconstrucción, 1-3. Glasgow: CCA: The Centre for Contemporary Arts.

New Museum. 2011. "Autoconstrucción, A Film By Abraham Cruzvillegas: Screening And Discussion". Podcast. https://archive.newmuseum.org/sounds/7646.

Roy, Ananya. "Slumdog Cities: Rethinking Subaltern Urbanism." International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 35, no. 2 (2011): 223-38. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01051.x.https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01051.x.

Simone, AbdouMaliq. "Afterword: Come on out, You're Surrounded: The Betweens of Infrastructure." City 19, no. 2-3 (2015/05/04 2015): 375-83. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1018070. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1018070.

Simone, Abdoumaliq. "The Politics of Urban Intersection: Materials, Affect, Bodies." 357-66. Oxford, UK: Oxford, UK: Wiley‐Blackwell, 2011.

Simone, AbdouMaliq. "People as Infrastructure: Intersecting Fragments in Johannesburg." [In eng]. PUBLIC CULTURE 16, no. 3 (2004): 407-29. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-16-3-407.

Sollins, Susan, and Susan Dowling. 2014. Legacy. Video. United States: Art in the Twenty-First Century.

Valette, Jean-François. 2018. "Land Regularization On The Fringes Of Mexico City: A Recipe For Reducing Inequalities?". Metropolitics.

Ward, Peter M. "Intra-City Migration to Squatter Settlements in Mexico City." [In eng]. Geoforum 7, no. 5 (1976): 369-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7185(76)90069-5.

Wissel, Christian von. Dwelling Urbanism : City Making through Corporeal Practice in Mexico City / Christian Von Wissel. Basel : Birkhäuser, 2019.