Grass, Asphalt, and Sky: Affects of the Void

Marie Detjen

Urban voids and wastelands are often felt as signs of economic depression and declining populations. In the rapidly growing and densifying city of Berlin, however, they have become a rare and coveted luxury. One of its last remaining voids is the defunct "Tempelhof Airfield”, a vast, entirely empty expanse in the middle of Berlin. While resisting and offering respite from the building-frenzy and commercialisation that afflict the rest of the city, it also raises anxieties about housing shortages and gentrification. Using the case study of Tempelhof Field, this essays explores how urban political discourses manifest affectively in empty spaces. In turn, the void itself comes be understood as both an affective and discursive field on and through which Berliners negotiate what a good life, and a good city, should look like.

INTRODUCTION

On a map of Berlin, Tempelhof Airfield stands out. Just south of the city centre it glares as a gaping green void. With 386 ha it is the biggest urban green in Germany, bigger than Hyde- or Central Park. The experience of entering the field for the first time is accordingly striking. Between the bustling streets, the sky suddenly opens up. It gradually widens as one walks down Herrfurthstraße towards the East entrance of the field until, suddenly, there seems to be nothing but sky. Sky, and beneath it, a spectacular vastness of grass and asphalt. Far in the distance, the city reappears as a faint and familiar skyline. Apart from the crowds of people (depending on time and weather), the field is breath-takingly empty: no buildings, no park benches, no trees, not even streetlights obstruct the view.

Every time I enter the field I can observe, in myself and the people around me, a change of mood. A weight seems to fall off, breathing becomes deeper. Often, people suddenly walk slower (or, if they are runners, start jogging). Even on a rainy December day, as when I came to take the photos for this piece, the field can appear as a lighter, better world. In summer, however, it feels downright utopian. Groups gather on the grass for barbecue parties, sunbathing, acrobatics, reading circles or ball games; they skate, run, and cycle on the rollways. Unexpected things can happen: men in suits lie in the grass and start looking at the clouds. Someone takes out a speaker, or a guitar, and spontaneous dance parties begin. Strangers start a conversation. Skateboarders attach large kites to their longboards launching a “kite-boarding” craze (Gauto 2011), while in winter, without any official initiatives from authorities, part of the field turns into a cross-country ski trail. Berliners, who are notoriously ill-tempered (Pearson 2014), suddenly get into a good mood. They feel free. As a kiteboarder put it: “When I roll over the field – in the middle of the city – to me, that’s absolute freedom”. A jogger in the same newspaper article observes that “as soon as I’m here and see as far as the horizon, I feel free – from stress, from everyday life…” (Frenzel 2014, my translation). This essay will ask: how is this “affect of freedom” produced, how can it be studied, and what are its political implications?

In his sociological study of the Tempelhof field as an “iconic liminal place”, Dominik Bartmanski argues that, to understand the lasting social support for keeping the field empty despite various pressures to build, we have to look at its spatial materiality, refocusing “analytical emphasis from political intent to phenomenological content” (Bartmanski 2017, 216-17). Rather than disagreeing with this point, I want to expand on it. In linking back the phenomenological to the political intentions and discursive surrounds, I explore how the latter affect the way we feel on the field. The field offers respite from, but is also “affected” by, the pressures of and debates around it. This essay thus argues that urban political discourses manifest affectively in the material emptiness of the space, which becomes both an affective and discursive field on and through which Berliners negotiate what a good life, and a good city, should look like.

I will first give a historical overview of how Tempelhof airport transformed into “Berlin’s new urban commons” (Bartmanski 2017, 216). Secondly, I will sketch out how architects and anthropologists tend to conceptualise emptiness, suggesting that the reality of the field escapes both approaches. Thirdly, I argue that anthropological engagements with ruination, and especially Navaro-Yashin’s theorization of affective spaces, can be useful in understanding urban voids. Finally, I will show how the field as an affective space is both participating in, and produced through its political and discursive surrounds. My analysis throughout this essay is informed by ethnographic walks, informal interviews, and participant observation, which I conducted while living in the immediate vicinity of the field.

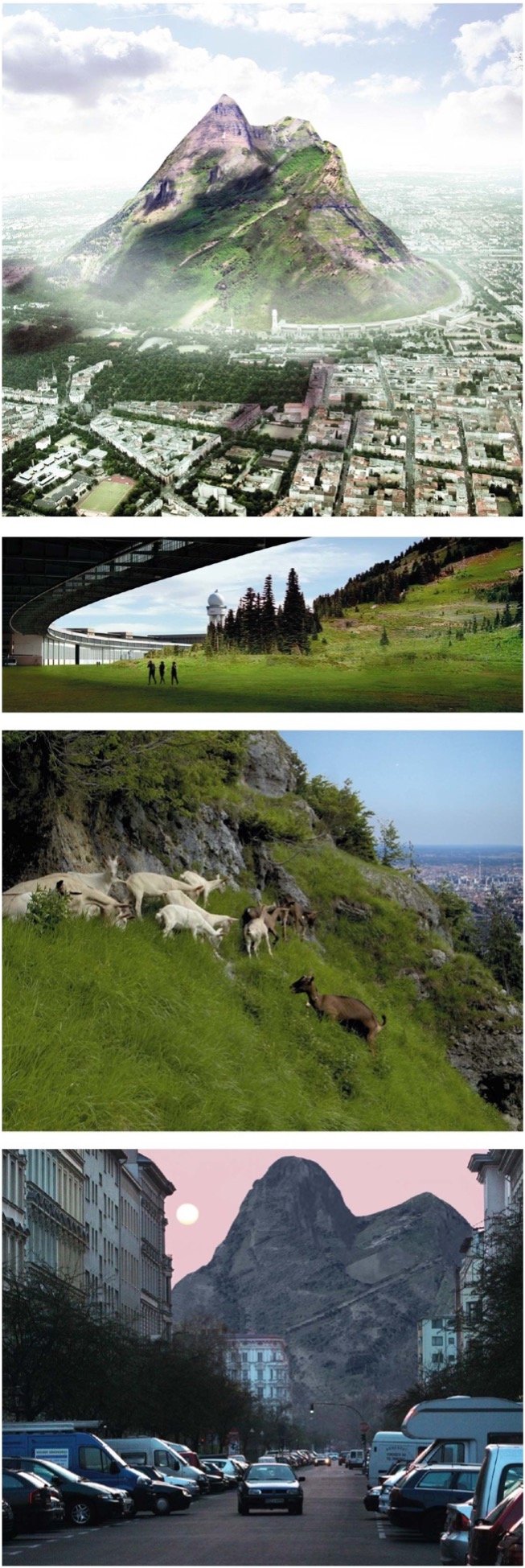

I. The Field

Since its construction in 1920, Tempelhof Airfield witnessed some of modern German history’s most important events. Under the National-Socialists’ plans to reconstruct Berlin as a megalomanic “capital of the empire”, the airport underwent a massive expansion, and from 1934 to 1936 partially accommodated a concentration camp. It further achieved iconic status as the landing site of the “airlift”, in which US and British troops flew supplies into West-Berlin during the 1948/49 Soviet blockade. After Germany’s reunification, the airport became increasingly obsolete, replaced by Tegel and Schönefeld airports, and finally shut down in Fall 2008 (Bartmanski 2017, 222). Another two years passed before activists, through demonstrations and a temporary occupation, achieved the official opening of the field to the public. Meanwhile, city government as well as architects across the country began hatching out “development plans”. Some suggested erecting an artificial mountain, others a lake or amusement park (Martens 2021). At the same time, residents started so-called “pioneer-projects” on the newly opened field, many of which still run today, such as an urban garden and a minigolf course. In 2013, the Berlin Senate finally revealed its own development plan, which envisioned a mixture of green area, apartment buildings, commercial sites, and an “innovation park” (Kaschuba and Genz 2014, 5). At this point, however, residents of the neighbouring Schillerkiez-neighbourhood had already started a citizen’s initiative called “100% Tempelhofer Feld”, which campaigned and collected signatures for a city-wide referendum aimed to legislatively block the senate’s plan. Against the panicked warnings of real-estate companies, and against a massive state-funded counter-campaign, the initiative succeeded: a vast majority voted against the development, and a law was passed that would henceforth bar the senate from building, developing, or even replanting the field in any way, apart from basic maintenance (DIE WELT 2014). While calls for a development re-emerge regularly, the field has become Berlin’s most popular park, with around 200.000 weekly visitors in summer 2021 (Jericho 2021).

II. Theorising emptiness

Empty space can elicit vastly different affective responses. An empty warehouse in a demographically declining post-industrial town is likely to exude an affect of depression and deprivation, while the physically same warehouse in a trendy urban neighbourhood will seem elegant and luxurious, promising industrial-style galleries, or loft-apartments. The white, empty rooms of the White Cube would immediately lose their elitist chic if they belonged to the cleared-out shops of a bankrupt shopping-mall. Urban studies and architectural engagements with empty space have long focused on the design aspect – the void of the White Cube, thereby, is chic because it is designed, intentional, whereas the stripped shop is involuntarily empty (Dissmann 2011, 46). The former is functionally empty, whereas the latter’s emptiness is indicative of its very loss of function. While intentional emptiness epitomizes luxury, undesigned emptiness means deprivation and decline. In the context of urban ecology, then, designed voids are “parks”, whereas undesigned voids are “fallow wasteland”.

This design conceptualisation of the affects and significations of emptiness fails to grasp the reality on the Tempelhof field. Its emptiness is not designed, it has lost its function as an airport, the aeronautic infrastructure lies fallow: in this way, it appears as wasteland. As a popular leisure area, however, it is highly “functional”, and not depressing whatsoever. Nevertheless, it is not a park either: Berliners, in my experience, refer to it exclusively as “the field”, and never as a “park”. The official name, evocatively, is “Tempelhof Freedom”, in the media it has been called a variety of names -- from “meadow-sea” by its supporters (Jacobs, 2010), or “meadow-desert” by those calling for development (Zawatka-Gerlach 2019), to, usually, the more sober “areal” or “former airfield”. The field thus defies the designed/undesigned, park/wasteland dichotomies. What, then, keeps it from becoming a park, and what from remaining a wasteland?

Here, ethnographic and anthropological insights are crucial. Only by thick description, by closely observing how people interact with the field and generate meaning from it can we understand its social nature. However, emptiness and urban voids are a recent and understudied field in anthropology. Notable exceptions who do explicitly explore the various manifestations and significations of emptiness (Dzenovska 2020, Frederiksen 2020, Gille 2020) focus on the category of left behind, deteriorating emptiness. Emptiness, in their analyses from Latvia, Greece, and Croatia, occurs when worlds end and new orders are not yet established or intelligible. There are important insights we can take from their theorisation: that emptiness is a “concrete spatial-temporal coordinate in the global landscape of capitalism and state power”, and in itself is “neither hope nor despair, but the potentiality of both” (Dzenovska and Knight 2020). In his study of how minor changes in a façade determine its categorisation as permanently empty or temporarily vacant, Frederiksen shows that emptiness is a malleable concept whose multiple significations are determined along culturally specific codes (Frederiksen 2020). However, the Tempelhof field, in a way, is the other side of the coin that these ethnographies describe: The socio-economic transformations that lead to the “emptying” of some spaces entail the “filling” of others, where emptiness disappears. In the case of rapidly growing Berlin, emptiness has become a luxury. As Huyssen lamented already in 2004, Berlin’s densification touches at the very identity of the city (Huyssen 2004). The interplay of WWII bombings and the Berlin-wall had cut through housing blocks and created extensive wastelands in the middle of the city centre (Dissmann 2011, 67). The Berlin I remember from my early childhood, thus, was full of empty land -- but every time I return, there seems to be less of it.

III. Affects of emptiness

How, then, can one study the affect of empty space? As I will show, recent anthropological engagements with ruins can provide important theoretical impulses. Stoler (2013) and Gordillo (2014) offer ethnographic accounts of how abandoned spaces hover between the revered status of romantic ruins, and unworthy rubble. This characteristic of ruins is shared by the urban void’s status between fallow, unproductive wasteland and luxurious free space.

For this essay, however, I will especially draw on Navaro-Yashin’s theoretical framework of ruination and affective spaces. In her ethnographic account of Turkish-Cypriot communities, who, in the aftermath of violent conflict, come to live in the ruined houses of displaced Greek-Cypriots, she explores the question of how “objects and dwellings” are implicated in transmitting an affect of melancholia, or Maraz (2012, 128-214). Are “affectivities projected onto ruins by subjects, or do ruins exude their own affect” (2009, 14)? In examining this question, she ponders and, in the end, reconnects supposedly divergent theoretical approaches, critiquing theoretical paradigm shifts that negate past theories and leave them behind as theoretical ruins.

Firstly, Navaro-Yashin discusses the paradigm of Actor-Network-Theory. Against Latour’s model of a neutral, transcendental network of human and non-human entities, Navaro-Yashin argues that the network is historically contingent and politically specific (Ibid, 9). Following Marilyn Strathern, she suggests that the pervasiveness of the Network, in her case study, is “cut” by sovereignty. In my study, it is cut by debates and developments of urbanism, just as the flatness of the field is cut, on its edge, by the verticality of the surrounding city. The relation between space and people on the field thus must be located in the economic, political, social, architectural, and demographic specificities of Berlin.

Secondly, Navaro-Yashin interrogates the “affective turn,” and Deuleuze and Guattari’s notion of affect as “the non-discursive sensation which a space or environment generates” (Ibid, 13). However, she finds that blending out language and subjectivity would ignore her ethnographic finding that “subjectivities were shaped by and embroiled in the ruins which surrounded them” (Ibid, 15). Rather than limiting analysis to the linguistic or subjective domain, Navarro-Yashin escapes this theoretical see-saw by proposing that “tangibilities transmit affect, but this affect is mediated and qualified by the knowledge that the people who come into contact with them have about the context for the objects” (2012, 212). Following this theoretical framing, I suggest that urban voids are an affective space that is created through the interplay of materiality and subjectivity, spatiality and representation. Rather than privileging its physical properties, or discursive surrounds, they should be studied as interrelated.

III. The good city life

In 1910, Karl Scheffler famously described Berlin as a “city condemned forever to becoming and never to being” (Mair and Zaman 2020, 72). With Tempelhof field, Berliners finally have a place where they can “just be”, while the rest of the city keeps becoming and changing. As I will now show, however, the city’s “becoming” and the field’s “just being” are, affectively and discursively, closely interlinked.

Kerstin Meyer, one of the activists of the “100% Tempelhof” campaign, seven years later wrote an account of Tempelhof’s “defence”, in which she describes the spatialised experience of the field as a shared political experience “… like marching together for a cause, though here we don’t march, we can just be—and here we can grow conscious, collectively, of land and soil in the metropolis, and of our temporary use of it. (Meyer 2020, 103). The title of her piece is USE-LESS-LAND, playfully turning the supposed “uselessness” of the land, bemoaned by Senate and real-estate developers alike, into a call to “use less land” – less land for commercialisation, for the incessant building boom, for unnecessary and highly problematic representational projects such as the recent reconstruction of Berlin’s imperial “City-castle” (Wainwright 2021). Through its material emptiness, the field not just represents, but is an antipode to such developments. Here, one can “just be”, without cars, shops, or advertisements. The material emptiness of the field proposes an alternative vision of the city, and by “just being” on the field, by enjoying its purposelessness and emptiness, Berliners shape, explore, and articulate their own visions for what city life could look like, outside of capitalist imperatives of buying, selling, growing, and using. The only people building or growing anything here are the urban gardeners, who themselves explore alternative forms of production and agriculture, “commoning”, and grassroots democratic organisation. The materiality of the garden equally sets an explicit opposition to ideals of rationality and perfection: it is improvised, unfinished, with skew beds and crooked structures. These alternative visions, then, are not logocentrically, but spatially and affectively conceived of and articulated.

At the same time, changes in urban political discourse can equally change the affective space of the field. One day, my neighbour, who has lived in Schillerkiez for 30 years and had himself collected signatures for the 2013 referendum, started to complain: somehow, the field had begun to feel “schickimicki” (fancy-schmancy), he now prefers to go to a smaller park nearby. Materially, the field has not changed since 2013. So, what happened? In his study of land clearances in Vietnam, Erik Harms found that “’clearing wastelands’ represents a process of knowledge production that literally wills a certain kind of emptiness into being” (Harms 2014, 313). Through discursive operations reminiscent of the colonial concept of mise en valeur, “wastelands are not so much discovered as made” (Ibid). Possibly, then, the opposite process can also occur: wastelands can be “domesticated”, routinised, pulled out of their liminality and purposelessness into the capitalist order.

The emptiness of the field is discursively put into question: The scarcer living and building space becomes, the more emptiness seems like a questionable luxury. In Berlin, pressure to build is immense, not just from estate companies, but also for social housing and to accommodate the 10% population increase between 2011 and 2019 alone – in the same time frame, the housing stock increased only by 5% (Tagesspiegel 2021). Further pressure stems from the fact that the neighbourhoods adjoining the field are rapidly gentrifying ever since its opening. Some of those who campaigned in 2013 may now be pushed away by rapidly rising rents, attributable to the attractive green space and the absence of aviation noise. While rent-regulations kept my neighbour’s rent low, newer cafés and restaurants are mostly unaffordable to him. The opening of the field as an inclusive, non-commercialised space has accelerated the commercialisation and exclusivity of the surrounding neighbourhoods. I don’t suggest that this routinisation is complete, and that the field has lost its subversive edge. Only last year, it became a main site of mobilising and collecting signatures for a citizens’ initiative, itself inspired by the 2013 “100% Tempelhof” initiative, which successfully campaigned for a referendum to expropriate Berlin’s biggest estate companies (Butland 2022). Both examples show, however, that the subjects who are experiencing the field are thinking and talking about gentrification, about evictions and rent caps. They may be even more triumphant for having withheld this vastness from capitalist expansions, or gauge anxiously how much housing it could contain, or feel alienated by the flocks of tourists and hipsters. The affect of the field, in any case, is not merely exuded by the material properties of its emptiness: the discursive and political surroundings of the field play themselves a central role in shaping and producing it as an affective space. As I have shown under II., empty space, by nature of being empty, is particularly malleable and can come to mean vastly different things. The field’s affect, then, is just as instable as its position in urbanist discourse.

Conclusion

Tempelhof field is embedded in a rapidly changing urban landscape. In their vanishing, voids in Berlin have undergone a radical transformation: From derelict wasteland to a precious and contested site. The remaining voids hold the ghost of the Berlin that once was -- they contain the memory of the empty spaces that are disappearing. But they also point to the future, as materialised visions of alternative city life. Whether populations are shrinking or exploding, then, voids become a ground on which the most pressing questions of urban life and global capitalism are felt and negotiated. As I have shown, the materiality of and the discourse around emptiness are inextricably linked to produce divergent affective responses. Beyond these theoretical considerations, however, I tried to show that voids and wastelands are a valuable social space of their own right, and should be recognised as a complex source of social knowledge. Moving away from a heavily architecture-focused study of the built environment, they invite further inquiries into how emptiness is produced, maintained, valued, and experienced.

References

Bartmanski, Dominik. 2017. “A Temple of Social Hope? Tempelhof Airport in Berlin and Its Transformation.” In National Matters: Materiality, Culture, and Nationalism, edited by Genevieve Zubrzycki, 216-240. Stanford: Stanford UP.

Dissmann, Christine. 2011. Die Gestaltung der Leere: Zum Umgang mit einer neuen städtischen Wirklichkeit. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag.

Dzenovska, Dace. 2020. “Emptiness: Capitalism without people in the Latvian countryside.” American Ethnologist 47: 10-26.

Dzenovska, Dace, and Daniel M. Knight. 2020. "Emptiness: An Introduction." Theorizing the Contemporary, Fieldsights, December 15. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/emptiness-an-introduction.

Frederiksen, Martin Demant. 2020. "Emptiness and Surface." Theorizing the Contemporary, Fieldsights, December 15. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/emptiness-and-surface.

Gordillo, Gastón. 2014. Rubble: The Afterlife of Destruction. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Harms, Erik. 2014. “Knowing into oblivion: Clearing wastelands and imagining emptiness in Vietnamese New Urban Zones.” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 35: 312-327.

Kaschuba, Wolfgang and Carolin Genz. 2014. Tempelhof. Das Feld: Die Stadt als Aktionsraum. Berlin: Institut für Europäische Ethnologie.

Lehner, Judith M. 2021. Die urbane Leere: Neue disziplinäre Perspektiven auf Transformationsprozesse in Europa und Lateinamerika. Berlin: Jovis Verlag.

Meyer, Kerstin. 2020. “USE-LESS-LAND: Two centuries of defending Tempelhofer Field in Berlin.” In USELESSNESS: Humankind’s most valuable tool?, edited by Michelle Howard and Luciano Parodi, 94-105. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter.

Navaro-Yashin, Yael. 2009. “Affective Spaces, Melancholic Objects: Ruination and the Production of Anthropological Knowledge.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 15: 1-18.

Navaro-Yashin, Yael. 2012. The Make-Believe Space: Affective Geography in a Postwar Polity. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Stoler, Ann Laura. 2013. Imperial Debris: On Ruins and Ruination. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Images

Brosch, Martin. Tempelhofer See. 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2022, from http://tempelhofersee.de/infos.html.

Google. [Satellite view of south-central Berlin]. N.d. Retrieved January 7, 2022, from https://www.google.com/maps/@52.4864187,13.4003014,8102m/data=!3m1!1e3.

Mila Berlin. The Berg. N.d. Retrieved January 7, 2022, from http://www.the-berg.de/the_berg.html.

Newspaper/Blog Articles

Butland, Phil. 2022. “Fighting gentrification in Berlin – the experience of Deutsche Wohnen & CO Enteignen.”Peoples Dispatch, January 4, https://peoplesdispatch.org/2022/01/04/fighting-gentrification-in-berlin-the-experience-of-deutsche-wohnen-co-enteignen/.

DIE WELT. 2014. “Berlin entscheidet sich gegen Tempelhof-Bebauung.” Die Welt, May 25, https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article128404068/Berlin-entscheidet-sich-gegen-Tempelhof-Bebauung.html.

Frenzel, Veronika. 2014. „Volksentscheid Tempelhofer Feld: Die durchregulierte Freiheit.“ Der Tagesspiegel, May 23, https://www.tagesspiegel.de/themen/reportage/volksentscheid-tempelhofer-feld-die-durchregulierte-freiheit/9936188.html.

Gauto, Anna. 2011. „Flughafen Tempelhof: Das Paradies der Anarchosportler.“ Die Zeit, August 17, https://www.zeit.de/sport/2011-08/flughafen-tempelhof-parksport.

Jericho, Dirk. 2021. „Tempelhofer Feld beliebter Freizeitpark im Coronajahr.“ Berliner Woche, May 27, https://www.berliner-woche.de/tempelhof/c-umwelt/tempelhofer-feld-beliebter-freizeitpark-im-coronajahr_a311151.

Martens, Janina. 2021. “Hoch hinaus in Tempelhof: Wie Berlins Ex-Flughafen die Fantasie beflügelt.” Der Tagesspiegel, April 5, https://www.tagesspiegel.de/berlin/hoch-hinaus-in-tempelhof-wie-berlins-ex-flughafen-die-fantasie-befluegelt/27059688.html.

Pearson, Joseph. 2014. „The Rise and Fall of Berliner Schnauze.” The Needle, April 26, https://needleberlin.com/2014/04/26/the-rise-and-fall-of-berliner-schnauze/.

Wainwright, Oliver. 2021. Berlin’s bizarre new museum: a Prussian palace rebuilt for €680m.” The Guardian, September 9, https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2021/sep/09/berlin-museum-humboldt-forum.

Zawatka-Gerlach, Ulrich. 2019. „Wiesenwüste mit breiter Betonpiste: Es wird Zeit, am Tempelhofer Feld nachzubessern.“ Der Tagesspiegel, June 24, https://www.tagesspiegel.de/berlin/wiesenwueste-mit-breiter-betonpiste-es-wird-zeit-am-tempelhofer-feld-nachzubessern/24484848.html.