Observing Boundaries in the public Toilet

Cecy Park

This essay demonstrates the public toilet as a space that actively acknowledges boundaries of hygiene and privacy, based on fieldwork conducted in toilets in various locations on UCL Bloomsbury campus. The first section ‘Boundaries of Hygiene’ discusses the taboo of ‘dirt’ associated with bodily excretion and the space of the toilet, with fieldwork focusing on materiality and infrastructure. The second section ‘Boundaries of Privacy’ sheds light on the multi-sensory experience of the toilet, as it is explored how different senses contribute to perceived privacy. By critically examining the boundaries that hold up the public toilet as built environment we inhabit, it is possible to understand what kind of corporeal politics it reinforces.

This essay demonstrates the public toilet as a space that actively acknowledges ‘boundaries.’ This includes physical boundaries, spatial separation created by material and architectural structure, and metaphorical boundaries, notably the sense of distance that exists in the concept of hygiene and privacy. As a built space that demarcates distance in both a physical and metaphorical sense, the public toilet rests upon and reinforces such notions of boundaries. At the same time, as a built space that is occupied and used by people, such boundaries inescapably extend to the bodies that occupy them. Especially because urination and excretion are mostly universal acts and acts wherein people experience intimate contact with bodies, the toilet, which is a designated space for such acts, is a crucial space in defining key ideas about the human body. The ‘publicness’ of the public toilet furthers certain learnings of the body as the presence of others in the shared space enables sense and practice of surveillance and regulation. Therefore, by critically examining the boundaries that hold up the public toilet as built environment we inhabit, it is possible to understand what kind of corporeal politics it reinforces.

The first section ‘Boundaries of Hygiene’ employs Mary Douglas’ concept of pollution and ‘dirt’ to explain the taboo surrounding bodily excretion and the toilet (2002). Joined with a discussion of materiality and infrastructure, this section shows how the space of the public toilet builds upon its own notion as a space of hiddenness and shame. The following section ‘Boundaries of Privacy’ troubles the perceived privacy in the public toilet, revealing the primacy of vision in the concept of privacy that can be observed in cubicle partitions. Pointing out the multitude of shared senses between users, this section also examines the policing of acts within the toilet as a social space.

In each section I include an account of my own fieldwork conducted in toilets in various locations on UCL Bloomsbury campus to illustrate how the boundaries are materialised in the built environment. While I acknowledge that this is far from a sample of public toilets in general and the demographic of users are extremely limited, this location is useful in that UCL is an institution that has made effort over the years to show commitment to creating an equal and inclusive environment and thus provides a selection of models of toilets, allowing for an assessment of the implications of boundaries of the public toilet in their multiple forms. The sample of toilet spaces which I conducted fieldwork in comprises of toilets assigned women’s and gender neutral, which I found most accessible to my socially presented self as the researcher. Thus this essay includes no first-hand account of toilets assigned men’s, crucially toilets with urinals. In addressing such toilets, I rely on second-hand accounts conducted by researchers that have had access. The methodology used for fieldwork is informed by sensory anthropology that focuses on the overlapping of multiple senses within experience, as Howes sets forth explaining ‘intersensoriality’ (2005: 9). This methodology is meaningful in that it allows for an ethnography that more fully encapsulates the sensory experience of the space that is subject of research. Attached as visual aids are photographs taken by myself, under a strict rule of taking photos only when no one else is present in the toilet, in order to prevent causing discomfort in others. While vision is a large and evident part of experiencing hygiene and privacy within the toilet, the textual account of fieldwork conducted for this essay also heavily engages in sound, smell and touch.

Boundaries of Hygiene

The idea of the long-winded route to the toilet is apt to describe its place in conversation and concept as well as physical location. Various euphemisms are used to address the toilet to avoid allusion to the function of the space, even the term ‘toilet’ itself deriving from the French ‘toile’ which means cloth or dressing (Stead 2009: 128). Calling toilets ‘ladies’ and ‘gents’ relies on the characteristic binary gendered division of public toilets (Stead 2009: 130). There are also shared cultural expressions of cryptic excuses such as ‘to water the lawn’ or ‘to spend a penny’ (Stead 2009: 130). The necessity of using such euphemisms comes from the close association of the toilet space with the action that happens within. In other words, the taboo of discussing defecation extends to a taboo of discussing the space within which it happens. Mary Douglas’ study of ‘dirt’ in Purity and Danger is useful in understanding the taboo of defecation (2002). Douglas distinguishes the opposing realms of the pure and the polluted and argues that this structure acts as a system of order and classification that fundamentally affects human perception and practices (2002: 3). Yet there necessarily appear matters that threaten the stability of order by breaching boundaries, or being ‘out of place,’ which Douglas identifies as ‘dirt’ (2002: 44). Because dirt creates anxiety and offence upon appearance, society generates ways to either classify or eliminate it (Douglas 2002: 48). Bodily waste being a substance of pollution, it would be considered dirt upon breaching its boundaries, and hence it is assigned status of taboo in society, fear of shame inhibiting its exposure in the public arena. The symbolic classification of bodily waste as pollution extends to classification of the toilet as a polluted space, bringing with it the sense of danger and shame upon contravention of order.

In effect, even the cleanest of public toilets become, culturally speaking, a “dirty space” (Barcan 2010: 25). Ruth Barcan proposes the idea that the public toilet is a space of concealment, “[providing] a literal and moral escape from the unacceptable” (2010: 34). In addition to the toilet’s being a space where one rids themselves of bodily waste, it is also a space where one rids of the idea of pollution that follows it. Hence it is important for the toilet to be perceived as being preserved as a ‘clean’ area in itself. Upon examining the materiality of the basement women’s toilet in the UCL Anthropology department building, I found extensive, smooth surfaces on all surface areas (figs. 1-2). Materials such as porcelain (toilet body and sink), glass (mirror), metal (lockers and radiator) and plastic (bin and toilet paper dispenser) are dense and airtight substances through which liquid or chemical particles cannot penetrate or linger. This allows quick and easy circulation of air, as well as frequent water-cleansing using anti-bacterial substances without fear of eroding of damaging fixtures. Also, because the visible deterioration of these materials is physical, such as chipping, bending or breaking, rather than chemical, such as growing mould, degradation of toilet fixtures over time does not hugely affect the perceived cleanliness of the space.

Fig 1 Source: author (2021). Image of inside cubicle in women's toilet, basement, UCL Anthropology department building.

Fig 2 Source: author (2021). image of open sink area in women's toilet, basement, UCL Anthropology department building.

My focus on perception is not to denigrate the importance of materiality in the actual hygiene of the space, as increased understanding of bacterial transmission and diseases has indeed influenced objects in many ways (Douglas 2002: 44). For instance, the bowl of the toilet fixture is designed so that water fills up the bowl as a barrier to prevent gas of flushed substances floating back up. Yet it must be noted that the material features of the toilet space that are distinct from the outside area contribute to users’ exposure to and thus habitual consumption of ‘signs of cleanliness’ (Barcan 2010: 37). Signs of cleanliness are perceived through multiple senses. Air fresheners used in toilets are frequently scented, not only replacing odour produced by activity within the toilet with a more pleasant fragrance but also signalling the removal and replacement of smell. The sound of the toilet flushing also bears association with the removal and replacement of water within the toilet bowl.

Fig 3 Source: author (2021). Image of toilet area facing door to main area, mezzanine floor, UCL Student Centre.

Fig 4 Source: author (2021). Image of toilet area outside stalls, mezzanine floor, UCL Student Centre.

Fig 5 Source: author (2021). Image of toilet area facing door to stairway, mezzanine floor, UCL Student Centre.

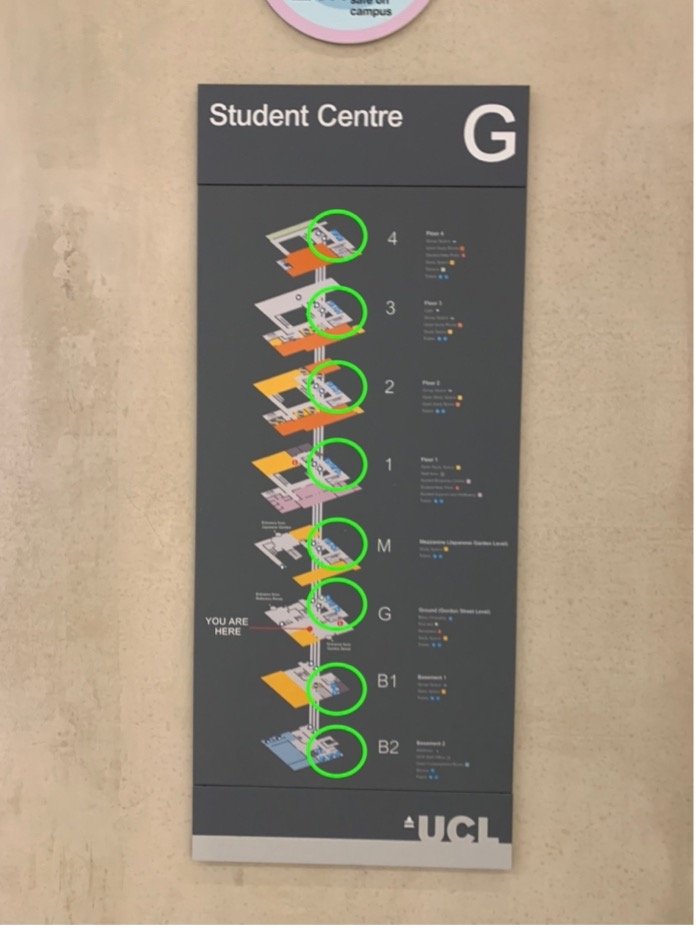

That the physical location of the public toilet is generally removed from the central sphere of activity within a building or area is consistent with such ideas of avoidance and concealment. The distance between polluted and non-polluted areas becomes quite literal. This can be observed in the UCL Student Centre, where the toilet can be found in an area between the main open area and the stairway, enclosed by doors on either end (figs. 3-5). Considering infrastructure, the decision of locating public toilets near outer walls or corners instead of central areas is not simply because of our regarding of bodily discretion as a periphery act, but also the mechanical fixture of pipes that is central to the function of toilets, which is to circulate fluids. The efficiency of pipes can be maximised by minimalising journey of liquid through the pipes. Hence, it makes sense to establish pipe fixtures in clusters, which allows for a whole area of toilets, urinals and sinks to be collectively conceptualised as ‘the toilet.’ For the same reason, if there are multiple floors, the toilet areas are situated in the same or similar spot, as can be seen in the floor plan for the UCL Student Centre (fig. 6). Such factors make the location of the toilet within a building generally presumable, thus saving much hassle and conversation over the avoided topic of toilets. The repetition of the symbolic separation in structure reinforces the idea of defecation as an act to be hidden from the public as well as allows direct confrontation to be avoided.

Fig 6 Source: author (2021). Image of floor plan with toilet area on each floor marked with circle, ground floor, UCL Student Centre.

Boundaries of Privacy

The act of bodily discretion being marked as an act of shame leads to its assignment as a ‘private’ and individual act where one engages in this activity individually, or with minimal help. As such, in building a toilet in the public sphere, it is considered essential to achieve privacy through creating a boundary that firmly separates the toilet user from ‘others.’ Yet it is the nature of shared public spaces that the sensed presence of the other cannot be fully eradicated. It is priorities in beliefs of privacy that allow the toilet space and following experiences to be perceived ‘private,’ rather than privacy itself being something that can be built into space.

Fig 7 Source: author (2021). Image of open sink area in women’s toilet, basement, Wilkins Building.

Fig 8 Source: author (2021). Image of corridor of cubicles in women's toilet, basement, Wilkins Building.

In Erving Goffman’s dramaturgical analysis of everyday life in the social sphere, the toilet is considered the ‘backstage’ region where one removes oneself from the ‘frontstage’ of ‘public performance’ in order to reassemble oneself before returning to frontstage (1956: 73). While this adheres well to the deeming of defecation as a personal and shameful act and thus the desired privacy that follows, in terms of the public toilet, it fails to recognise the high level of social activity outside of defecation that happens within the toilet sphere. Using Goffman’s theory and terminology in examining behaviour in the public toilet, Spencer E. Cahill et al suggests that in fact the toilet is physically divided into two distinct performance regions—the enclosed space of the stall as backstage and the unenclosed outside area as frontstage (1985: 36). This idea is more applicable to some models of toilets than others. For instance, in the basement women’s toilets of the Wilkins Building (fig. 7-8), the sinks being shared in an open area as opposed to toilet seats being separated in individual cubicles enables certain ‘interpersonal rituals,’ such as individuals’ performance of hygiene by washing hands and expressing disgust if this is obstructed in some way (Cahill 1985: 43). This is impossible in public toilet spaces where all fixtures deemed necessary for the entire toilet ritual are installed within one stall, such as the toilets on the third floor of the Mathematics department building (fig. 9) or toilets in the Student Centre (fig. 10). As a further example, although I was not able to investigate this matter myself, Cahill describes the experience of using adjacent urinals in men’s toilets in which the lack of physical barrier between urinals blurs the visible distinction between frontstage and backstage (1985: 41). Thus the boundary completely relies on social cues, such as ‘civil inattention, whereby one acknowledges presence of a fellow user yet noticeably withdraws attention to express lack of curiosity, is performed, or ‘nonperson treatment,’ where one treats another as if they are part of surroundings rather than a being (Cahill 1985: 41).

Fig 9 Source: author (2021). Image of inside cubicle in toilet, third floor, UCL Mathematics department building.

The significance granted to the establishment of the stall to install privacy within the public toilet area is heavily based on prioritising vision over all senses in creating privacy. This is not an original idea from Cahill’s study but rather it can be explained by the centrality of vision in assessing presence in the world, an idea that has dominated ‘Western’ thought for long. In effect, this brings efficacy of the stall structure, as Cahill’s study shows how individuals refuse to use unenclosed toilets where there exists the potential of the visual boundary of privacy to be broken (1985: 36). Yet upon examining the multitude of sensory experience that happens within the shared area of the public toilet, I came to question this sense of privacy, as whether inside or outside the stalls, the presence of others is never quite absent. I conducted this fieldwork inside a cubicle in the women’s toilet outside the Jeremy Bentham Room in the Wilkins Building, where I had a restricted view of what was happening outside as there was hardly a gap between the bottom of the stall door and the floor (fig. 11). From previous experience, I imagine I would have been able to see shadows of people in surrounding stalls or outside, perhaps even feet, had the gaps been larger. Yet what this restriction of vision allowed for me was a stronger focus on non-vision senses. From the cubicle, I was able to hear many sounds, including footsteps, chattering, the sink and hand dryer and a phone ringing. If vision and sound are indicators of timely presence of others, touch and smell allow an interaction that is perceived as more intimate, as they bring feeling of the bodily presence of others rather than knowledge of them. Though I did not experience the smell of bodily waste specifically while I was in this toilet for the purpose of conducting fieldwork, I have experienced this seeping through gaps between cubicles and while in the queue, thanks to air circulation. What I did experience instead was the instant smell of perfume that hit me when I first entered the cubicle, as well as the warmth on the toilet seat, both presumably left from a previous user.

Fig 10 Source: author (2021). Image of inside cubicle in toilet, mezzanine floor, UCL Student Centre.

Fig 11 Source: author (2021). Image from inside closed door of toilet cubicle in women's toilet, in front of Jeremy Bentham Room, Wilkins Building.

Like interpersonal rituals, sensory exchange between public toilet users happens in a different way according to how the toilet space is arranged. Using self-contained stalls, such as those in the Mathematics department building and the Student Centre, I noticed that smells did not seep out from within the stalls, but lingered quite strongly inside despite mechanical ventilation, as would be same for warmth as well, especially if the toilets were constantly occupied. Standing outside multiple self-contained stalls next to each other, I was able to faintly hear noise coming from the toilet flush and the hand dryer. From the inside, I was unable to hear anything, but this may have been due to the quietness of the outside area. This made me consider whether the lack of shared open space in the toilet area discouraged any sort of social interaction. Though my fieldwork is insufficient to reach such judgement, as it focuses on the space and surroundings rather than social interaction itself, the reduced element of homosociality within the toilet area due to the toilets’ being provided for all bodies instead of in accordance with binary gender may be an inhibiting factor of certain social interactions. Further research on this topic could be informed by studies on homosociality within gendered spaces and their implications.

Despite this abundance of sensory exchange, stalls are still perceived as a space ‘private’ enough to relax one’s body. Yet this sense of privacy by no means indicates freedom from bodily control. In Discipline and Punish, Foucault sets forth the idea of partitioning individuals into their own ‘monastic cell’ as a way of producing a docile, disciplined body (1995: 143). Truly, within the toilet space, one learns to embody the social and physical way of being. In a manner similar to observers in the model of the Panopticon which Foucault adopted and adapted in order to demonstrate mechanisms of control and power, the unknown and potential yet invisible presence of others outside of the toilet stall act to control behaviour of the user within; ‘The more numerous those anonymous and temporary observers are, the greater the risk for the inmate of being surprised and the greater his anxious awareness of being observed’ (1995: 202). The assumed presence of others outside of the stall may incline the toilet user more likely to flush the toilet, conscious of the exposure of noise to the outside. Influence of anonymous surveillance can reach further than actions and interfere with deeper bodily practices as well. Knowledge of presence of someone waiting outside the stall, perhaps through sound of shuffling footsteps or large sighs, may evoke anxiety and discomfort in the toilet user and impact control of release. As such, despite the boundary between individual bodies being key to its observance to the boundary between private and public, the public toilet is a site of active social bodily interaction and regulation that exceeds the material structure of the space.

Conclusion

This essay explores the boundaries of hygiene and privacy that undeniably have a large impact on the public toilet, in the way that it is constructed, perceived and experienced. In ‘Boundaries of Hygiene,’ I examined how the symbolic separation between purity and pollution operates in relation to the metaphor of pollution in the physical space of the public toilet. In ‘Boundaries of Privacy,’ I analysed the private and public within the toilet using ideas from Goffman’s dramaturgical theory of Foucault’s model of disciplining bodies. In the course of this, I incorporated my own fieldwork conducted in various toilets within UCL which allowed me to clarify how boundaries act within the space of the public toilet. By employing an analysis of materiality and infrastructure, I was able to demonstrate how the built environment is not simply granted meaning but that it also actively produces meaning. By employing a methodology of phenomenology in terms of sensory experience, I was able to illustrate the public toilet as a space that is occupied and embodied rather than simply a static material structure that is separate and distant from the human body.

References

Barcan, R. 2020. ‘Dirty Spaces: Separation, Concealment, and Shame in the Public Toilet.” In Toilet: Public Restrooms and the Politics of Sharing, edited by H. Molotch and L. Noren, 25-42. New York: NYU Press.

Cahill, E. S., W. Distler, C. Lachowetz, A. Meaney, R. Tarallo and T. Willard. 1985. “Meanwhile Backstage: Public Bathrooms and the Interaction Order.” Urban Life 14, no. 1 (April): 33-58.

Douglas, M. 2002. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concept of Pollution and Taboo (1966). London: Routledge.

Foucault, M. 1995. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (1975). New York: Vintage Books.

Goffman, E. 1956. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Social Sciences Research Centre.

Howes, D. 2005. “Introduction: Empires of the Senses.” In Empire of the Senses, edited by D. Howes, 1-20. Berg.

Stead, N. 2009. “Avoidance: On Some Euphemisms for the “Smallest Room”.” In Ladies and Gents: Public Toilets and Gender, edited by O. Gershenson and B. Penner, 126-132. Temple University Press.