Mapping Sociality in Structured Spaces: Understanding Boundaries in cattery blocks in an animal shelter

Qiqing Zhang

This essay examines the social dynamics between cats and humans within the highly regulated and segregated environment of an animal shelter in London, which prioritises hygiene and order. By exploring the high visibility in this space, the essay illustrates the concept of ‘flowing sociality,’ as discussed in Christine Helliwell’s study of the Dayak longhouse (1996). It analyses the permeability of architectural boundaries and the ambiguities of territories, showing how unstructured social interactions between cats and humans emerge through sound and light, even when they are physically separated. The essay focuses on three elements that constitute the physical and conceptual ‘home’ for the cats: glass, blankets, and human caretakers. It begins by addressing a dilemma created by the extensive use of glass: while transparency facilitates both cleaning and monitoring, it can increase stress levels for cats not accustomed to seeing other cats. In contrast, blankets provide a sense of home that transcends geographical boundaries, exemplifying the concept of home as a totality of senses (Petridou, 2001). Finally, by observing how cats scent-mark human caretakers, this essay challenges the rigid division between humans and their environment, proposing a mapping approach based on the empirical trajectories of interactions. Through participation in daily tasks at the animal shelter, I aimed to gain insights from the cats, to understand territories beyond geographical boundaries, and to perceive them as existential grounds.

Introduction

We live in a world that is mapped out by various ‘sophisticated means of cartographic information’ (Aureli, 2019, pp.154), and these boundaries seem to grow increasingly rigid, whether they separate nations, communities, or species. Proposing an alternative perspective based on ‘chain of practices’ (Latour, 2000, pp.11), Bruno Latour suggested that the material world ‘confronts us only to serve as a mirror for social relations‘ (Latour, 2000, pp.12-13), consequently, it becomes a network that is formed by ‘paths and trails’ (Latour, 2000, pp.12). When looking at animals living in urban areas, it is more evident that material structures are often permeated by unstructured social processes, creating a tension that persists even when boundaries seem rigid.

Domestic animals, especially pets, are carefully structured by humans. We decide where they should live, what they should eat, and how they should behave, reflecting a human desire to maintain order and predictability in relationships with animals. This structure is even more evident in animal shelters, where animals are carefully assessed, separated, conditioned, and distributed. These shelters are designed to prevent the chaos that humans assume non-human species might cause in urban settings without proper management. They are institutions where ‘homeless’ cats can regain their ‘conditioned citizenship’ (Howell, 2015, pp. 3) and be ‘reunited’ with human households.

‘Why can these cats see each other so easily in their own units?’ This question came to mind immediately during my first volunteer session in the cattery at an animal shelter in London. A cattery is a section of the shelter dedicated to cats, divided into aisles, or ‘blocks’, with individual units where single cats or pairs reside (see figure 1). In this cattery, almost every cat is highly visible—to humans, other cats, and even, on occasion, dogs. As a cat owner, it is almost common sense that cats are territorial animals; when an unfamiliar animal invades their territory (RSPCA, last accessed 1st September 2024), it can cause stress. I was thus puzzled to see glass windows between the units in the cattery. I wondered why the shelter was designed with such high visibility in the first place. To what extent does the concept of territory depend on the visual presence of others? How are territories defined, both by cats and by humans? How do cats and humans exercise their agency in a space like this? How was the ideal home conceptualised in the narrative of an animal shelter?

To explore these questions, I will analyse three aspects: First, by examining the use of glass in architecture, focusing on how glass structures shape and are shaped by unstructured sociality in this shelter’s cattery. In contrast to the transparency of glass, blankets are widely used in the cattery as anchors for cats and their living environments, creating a sense of ‘home’. Finally, I suggest considering the human caretakers as 'walking territories' for cats, highlighting practical and cognitive aspects in mapping out territories, and examining the presumed division between human and non-human.

methodology

My observations of this cattery were gathered over approximately five months, with each volunteer session lasting four hours per week. My data collection involved participating in cleaning the cats’ units and hallways, washing dishes, filling out forms, socialising with cats, and talking to staff and other volunteers. I recognise that my analysis of cats, viewed from a human perspective and generalising them as a whole, carries inherent biases. Therefore, instead of ‘speaking for the cats’ or attempting to ‘see from a cat’s perspective’, this essay seeks to explore human perspectives on cats’ behaviour and examine how structured and unstructured interactions between different species are mediated through various materials in the built environment.

Figure 1: Indicative floor plan of cattery space

glass

Housing many cats under the same roof requires careful planning. The shelter I volunteered at has 56 individual units, accommodating up to 80 cats simultaneously, excluding those in foster homes. This is a considerable number given the shelter’s scale, so the space allocated to each cat is limited. The individual units are designed to resemble ‘lofts’, each with two storeys connected by a small staircase and a top shelf to create more vertical space. All units measure less than a meter wide, making them quite confined from a human perspective. To mitigate this, glass windows between units allow views and light to pass through, providing a sense of openness in an otherwise confined area. However, this openness may not necessarily have a positive impact on the cats’ well-being.

Figure 2: Inner space of a cattery unit

‘Blocking these windows will be the first thing we do once we have the budget,’ explained staff member G, noting that some cats’ behaviour changed drastically when moved to units where they could see other cats. Even if they appeared indifferent, the increased stress manifested through over-grooming and redirected aggression toward human caretakers.

Figure 3: A blocked unit window

Glass is used extensively throughout the entire cat section. The cattery is first accessed through a wooden-framed glass door, and individual units also have glass doors. Glass windows are installed on the sides of each unit and on the lower level of the main block units, which face a garden where dogs play. The glass windows between units create almost a ‘tunnel of vision’: from one end of the block to the other, every window is precisely aligned, allowing a clear line of sight through the entire block.

Figure 4: Seeing through the windows

Architectural glass has been described as ‘a symbiotic combination of symbolic properties and actual material successes’ (Eskilson, 2018, pp.123). Pristine, freshly cleaned sheets of glass signify modernity, affluence, and the promotion of public health. Acting as a barrier to the outside world, the ‘impermeable surface of glass can be sanitised more effectively than other porous materials’ (ibid.). When French obstetrician Stéphane Tarnier introduced a glass-walled incubator to replace wooden enclosures, it was seen as offering ‘confidence to parents that the system was clean and technologically advanced’ (Eskilson, 2018, pp.124).

This symbolic perception of glass brings a sense of hygiene but also generates tension between care and surveillance. Besides intensive care for infants, glass can also bring ‘hygiene to the outcasts of society’ (Eskilson, 2018, pp.132). In The City of Refuge project, which provides shelter and services for the urban poor and homeless, Le Corbusier used glass bricks and glass curtainwalls to emphasise the symbolism of cleanliness and modernity (ibid.). This ‘incubator metaphor’ implies a certain level of incapability among the architecture’s inhabitants, whether they are infants, the urban poor and homeless, or stray cats. Stephen Eskilson argues, ‘in this manner the inhabitants were watched over and cared for like premature infants sealed in a glass box’ (ibid.).

Beyond hygiene, the incubator metaphor is also associated with the transparency of glass, providing visibility, which is essential for monitoring subjects inside the box. Foucault views architectural transparency as a facilitator of disciplinary control (Foucault in Eskilson, 2018, pp. 199), a notion that extends to pet keeping.

In these ‘glass incubators’, the animals we love and care for have little privacy. In the shelter, cats are continuously assessed until they are adopted. Glass doors and windows allow staff and volunteers to see where a cat is before entering its unit, reducing the risk of escape. A cat’s health and temperament can also be quickly assessed by looking through the glass doors. As a volunteer, I was instructed to fill out forms regarding food and water consumption, fecal conditions, and any unusual behaviour. The use of glass facilitates this close monitoring of cats’ behaviour and well- being, promoting ideals in pet care suggesting that a ‘good keeper’ is someone who attends to and understands a cat’s needs.

Philip Howell argues that placing animals in confined spaces—whether urban zoos, animal shelters, or pet-owning households—creates a ‘modern, capitalist culture of alienated nature’ (2015, pp.7). This approach serves as a reminder that animals living close to humans have their environments planned and regulated by us. In the context of the shelter, cats abandoned by their owners are relocated from one carefully designed space to another, and placed into social structures dictated by the architecture.

Humans’ perception of cats as independent and territorial (RSPCA, last accessed 1st September 2024) has led to the cattery being divided into small units. From G, a cat behaviourist’s perspective, transparency in cattery units can stress cats. However, from an anthropologist’s point of view, it might contribute to what Christine Helliwell calls a ‘fluid and unstructured sociality’ (Helliwell, 1996), allowing for visual and acoustic interaction among cats, humans, and even other species. The setup of the cattery blocks is akin to the Dayak longhouse in Helliwell’s work, where residents can see each other’s shadows and even converse through walls of sheer curtain (ibid.). Due to the transparency of glass, socialising with a single cat often involves interactions with other humans in the same space.

Casual conversations about a cat's recovery, food preferences, good or unwanted behaviours, stories of personal pets and life events, and adoptions occur through the airy structure of the blocks. Even when working alone, I rarely felt isolated because of the constant ‘flow of sound and light’ (Helliwell, 1996) from other parts of the building. This setup also became a form of supervisionthat promoted conformity. I realised that working in a transparent environment compelled me to behave more like a ‘good volunteer’. I began baby-talking to the cats in English, like the rest of the team, even though English is not my native language—I always speak Mandarin to my cat at home in London. I understood that everyone could hear everything in the cattery, so I wanted the rest of the team to hear me praising the cats, to show I was following the same practices, and to demonstrate that I was a good team member. This supports Helliwell’s assertion that ‘voices create a powerful sense of community’ (ibid.), which, in my case, helped create a sense of team through voice and language.

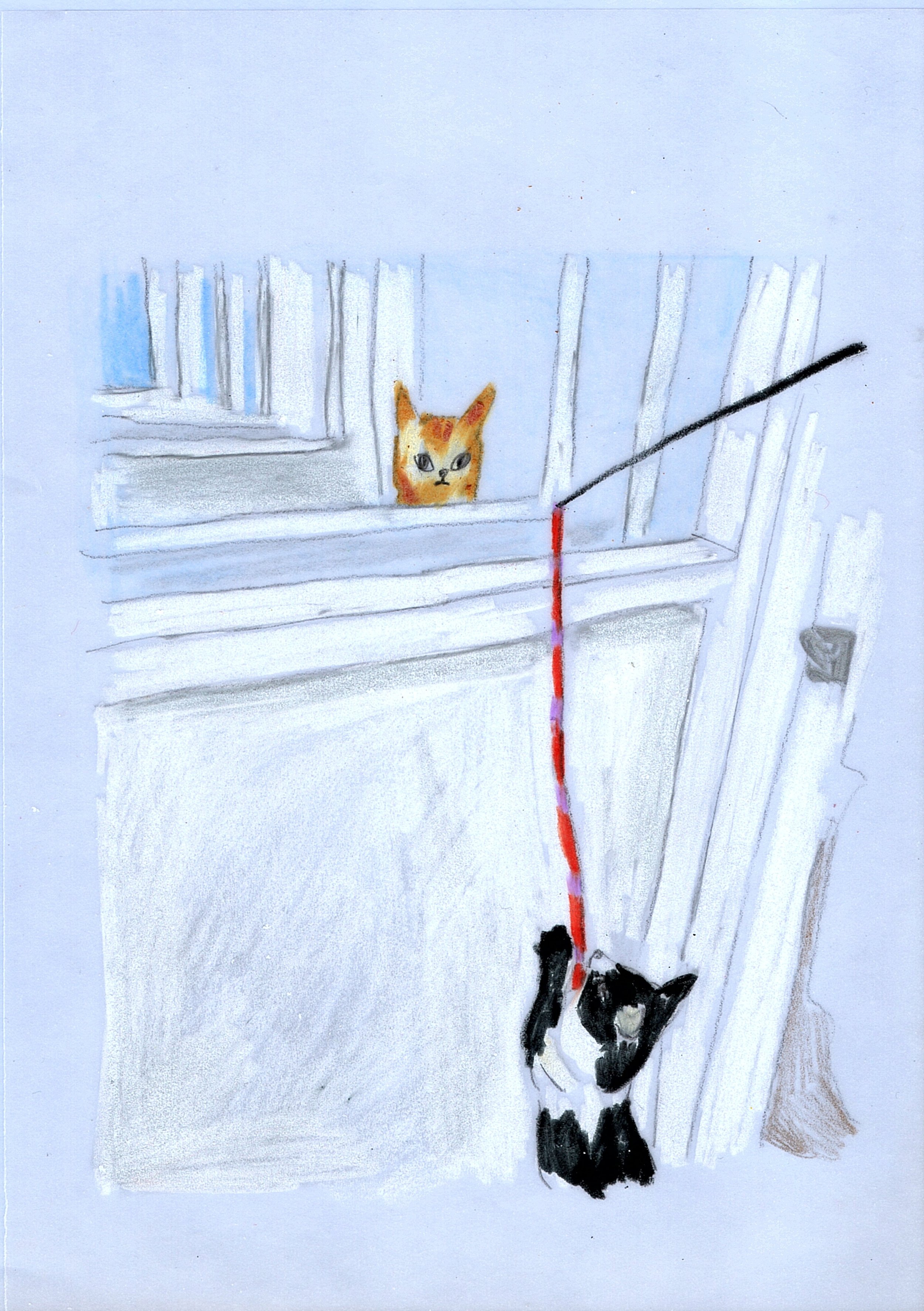

Compared to human staff, cats are even more intertwined in each other's lives during their stays at the shelter, even though they are separated initially and never placed in the same unit unless they are from the same litter or household. Neighbouring cats sometimes interact through glass windows, sharing the same toy or watching play fights in another unit. If two neighbouring cats are placed together in a confined space, at least one of them is likely to show some level of aggression toward the other. This unstructured sociality among neighbouring cats, contrasting with their separation upon arrival at the shelter, is facilitated by the transparency of glass while being confined by its impermeability. These interactions, as Helliwell noted in the ‘tapestry of sound’ in the longhouse, are ‘never forced, never demanding of participation’, creating ‘a companionship constantly at hand’ (1996).

Figure 5: Cats’ interactions through glass

Blankets

The shelter has a large collection of donated blankets, including towels, fleece, cotton and linen bedsheets, cushioned pet beds, and more, adding warmth and softness to the standardised space. Thanks to their versatility, blankets have acquired a greater role: human actors can select different blankets based on their preferences and assumptions about the cats, while cats use these absorbent materials to leave their scent, scent-marking the units as their own territory.

Unlike the incubator metaphor, some cats require more ‘privacy’ to maintain their well-being, such as those with neurological conditions, illnesses, or nursing mothers. To help reduce stress, the cattery team sometimes covers windows and unit doors with sheets to block unwanted onlookers. In feline body language, staring into a cat’s eyes can be perceived as a threat, leading to fear and anxiety, while breaking eye contact indicates trust and relaxation. In this sense, reducing visibility by covering windows and doors with opaque materials can create a safer, less stressful environment.

We often understand care as an activity undertaken to maintain and protect a person or thing (Fennell, 2015, pp.3). The characteristics of blankets symbolise the qualities of care—they are soft, warm, and fluffy, in contrast to the texture of glass. Thus, giving a blanket to a cat signifies the. attentiveness of the human caretaker. This relationship is evident in the interactions between staff member M and a 10-year-old black-and-white cat named Luke, who was found in poor condition. Upon arrival, Luke’s hair was dirty and tangled from head to tail, he had a lump in his jaw that required surgery, one of his eyes had to be removed, and his fore paws were also wounded which gave him a wobbly walking posture. Staff member M, who is very attentive to Luke, expressed her delight when she saw him immediately start ‘making biscuits’ on a fleece blanket she had given him. She said, ‘It almost felt like that was the first blanket he’s ever touched in his whole life...and he was like: “Oh my god, what is this? It feels so soft!”’ M’s voice was filled with excitement, and she gestured to mimic Luke’s ‘biscuit-making’ motion. In cat behaviour, ‘making biscuits’ refers to a ‘kneading motion cats make with their paws, signifying that they feel safe and content in their environment’ (ASPCA.org. Accessed 1st September 2024). Luke’s reaction to the blanket reassured M that he felt safe and relaxed, and that she was doing a decent job as his caretaker.

Blankets in these units act as ‘home objects’ for cats, whereas a home is not necessarily tied to a geographical location; it is the totality of senses (Petridou, 2001, pp.89) evoked by fragments. In one instance, two cats were cared for at the shelter while their owner was hospitalised, with the expectation they would return home afterward. A sign on their unit door read ‘Please do not remove: pink and knitted blankets’, while for resident cats awaiting adoption, blankets are changed when they seem dirty. Although those specific items belonged to the cats’ owner and were to be returned with them, the cats’ attachment to these blankets highlighted their importance in creating a sense of home. During a routine cleaning, I tried to wipe the surfaces under these cats’ blankets, but one of them kept following my movements, obstructing my work. While I interpreted this as affection, staff member C, who saw us through the door, remarked, ‘They seem worried when you move things around.’ These cats that have a home seem to be tied to their belongings from home, in contrast to the changeable blankets for shelter cats. In the same way that food can ‘evoke in a unique way the sensory landscape of home’ (Seremetakis in Petridou, 2001, pp.89), scented blankets for cats can do the same, helping to restore fragmentation by providing a ‘return to the whole’ (Sutton in Petridou, 2001, pp.89), and contributing to the process of creating a sense of self (Petridou in Miller, 2001). The fact that cats can become obsessed with their blankets supports this notion; it helps them maintain routines, forming a sense of self in an unfamiliar shelter space through scent marking. Despite cats’ attachment to their home environment, a sense of belonging and stability is constructed by these portable fragments rather than a concrete geographical location.

A ‘home’ is where a domestic animal is intended to reside: living with at least one human under the same roof and surrounded by warmth and familiar objects. The shelter has undergone several name changes since its founding, with each rebranding reflecting a continued emphasis on the concept of ‘home’, before adopting its current name in 2012. Apart from the shelter’s name, the concept of ‘home’ is also deeply ingrained in the language of animal rescue. An animal abandoned by its owner is labeled ‘homeless’ and is often placed in an ‘animal home’ or ‘foster home’, terms that indicate temporary care without explicitly acknowledging their transience. Conversely, upon successful adoption, the animal’s new residence is termed a ‘forever home’, suggesting permanence, though the reality may differ, as some adopted animals end up back in shelters due to integration issues. This suggests that cats residing in all types of ‘homes’ are actually highly mobile. At the shelter in my research, cats arrive in units designated for quarantine for at least a week, then move to the blocks for their future residencies. From there, some are adopted from the shelter, some go to foster homes, and some return to the shelter after being fostered or adopted. Their life trajectories can vary significantly.

Analysing the notion of ‘home’ in terms of feline behaviour, it relates closely to the concept of territory. When I asked about the perception of cats being ‘territorial’, G explained that when a new cat arrives at its unit, the unit is not considered its territory initially. What she did not clarify was how long it takes for a cat to perceive the unit as its territory. I have seen cats adopted in less than two weeks, as well as those that have stayed in their units from the beginning to the time of writing this essay. At what point, and through what actions, does an unfamiliar space become a cat’s territory?

Moreover, the contradictions inherent in the concept of ‘forever’ in the context of animal shelters parallel those in an increasingly mobile human society. As we navigate the gap between ideals and realities, the concept of ‘home’ constantly evolves through a set of practices that emerge from material culture, constructed from fragmented senses of belonging.

caretakers

A built environment does not necessarily refer to architectural structures or natural landscapes; it involves relationships generated through interactions between the structure and actors. Attempting to integrate feline behaviour and building analysis, I propose the possibility that humans may become part of a cat’s ‘territory’ through being marked. To a cat, to what extent do humans differ from the rest of the environment? How is the concept of territory actualised by cats? These questions challenge the human-nonhuman separation in modern philosophy and align with what Latour has proposed about ‘disciplinary relations’ created by the material world (Latour, 2000, pp.19).

Cats are often perceived to be more attached to specific environments than to their human guardians. However, it is debatable whether human actors are truly separate from the environment. As discussed earlier, human caretakers actively contribute to providing elements of care, which is crucial for cats to maintain their routines. Thus, the ‘environment’ to which cats become attached refers to a network of routines ritualised through repeated practices and a consistent rhythm, involving interactions among various actors in the cat's life—whether they are the built environment, humans, other animals, or inanimate objects.

In daily operations at the shelter, tasks like setting up spaces, serving food and water, cleaning units, and interacting with the cats are all designed with the cats’ presence in mind. The shelter staff have thus developed specific body techniques to prevent chaos. For example, when opening a unit door, one must be mindful of the cat’s position, slide one foot in first to gently block the cat from escaping, then quickly squeeze in and lock the door behind while facing the cat. During cleaning, I was instructed to ‘keep them occupied’ by scattering treats or throwing toys into a corner, distracting the cats to allow for cleaning. If a cat nibbles on a caretaker, the recommended response is to stop interacting immediately and leave the unit to discourage further nibbling.

These techniques are shaped by the layout of the space, particularly the design meant to separate cats, which significantly influences their behaviour and, in turn, guides human actions. Through these practices, human actors mediate between the built structure and the cats, encouraging them to avoid open doors, associate humans with positive experiences, and refrain from biting. Moreover, shelter cats are confined to their units by architectural structures, human caretakers, and a culture that regulates the mobility of homeless animals, much like how human are confined to ‘patchwork of “enclosed” large-scale estates demarcated by fences and walls, making free roaming impossible’ (Aureli, 2019, pp.153). The walls that enclose the cattery units also limit a cat’s agency, preventing it from acting freely until it completes the adoption process and is placed in a ‘forever home’—another legitimised territory for the cat.

‘The concept of territory addresses the process of land appropriation’ (Aureli, 2019, pp.152). Cats define their territories not through geographic or political boundaries but through scent marking and related behaviours (DePorter et al., 2019). Domestic cats mark humans in the same way they mark any object— through body rubbing and scratching. When I enter a unit, the resident cat usually examines my calves, laps, hands, and forearms, then proceeds with a series of scent markings to cover the areas previously marked by other cats. A cat may notice the presence of other cats by detecting pheromones on my body, so the overlapping scents from different cats make me a walking territory—a platform for these separated cats to ‘socialise’ without actually contacting each other, and a mediator of the presence of various cats.

The way cats perceive their territories parallels that of hunter-gatherers. According to Pier Vittorio Aureli, hunter-gatherers did not conceive land as a surface with ‘lines’, but rather as a constellation of specific marks that served as both symbolic and physical orientation (2019, pp.152). These marks acted as ‘focuses’ (Peter J. Wilson in Aureli, 2019, pp.152). In contrast, territories in modern societies are typically represented through diagrams and data points. ‘Within the modern conception of territory, boundaries often mark possessions...with their exclusionary force derived from both the abstraction of scientific cartography and the power of law’ (Aureli, 2019, pp.156). This approach overlooks the empirical aspects of territory, while the modalities of hunter-gatherer and feline territory remind us that any attempt to map out spaces should be connected to individual memory, sensory experiences, and personal processes.

Conclusion

Referencing Howell’s comment on urban zoos, where animals are enclosed in ‘a variety of carefully controlled, thoroughly human-dominated spaces’ (2015, pp. 7), animal shelters share the same mindset when carefully placing animals in human households. The enclosures in this animal shelter reflect our perception of social interactions between cats and the roles we assign ourselves as both overseers and caretakers.

The high visibility in its architectural structure, achieved through the use of glass, aligns with ideas of hygiene and modernity. Yet allowing visual contact with other cats can increase stress levels for those cats that are not accustomed to living with others. The space is thus modified by staff members who attend to the resident cats regularly, reducing certain cats’ visibility by blocking windows and creating extra hiding spots. In this way, the actual space is constantly being adjusted and constructed with ‘temporary’ objects such as blankets, depending on the resident cats’ behaviours; the initial ‘mapping’ of the cattery space becomes meaningful only through these everyday practices and the cats inhabiting it.

In correlation with Helliwell’s concept of the ‘flow of sound and light’ (1996) observed in the Dayak longhouse, cats separated into different units in the shelter acknowledge each other’s presence and form a ‘flowing sociality’ (ibid.). Interactions within the cattery occur through glass windows. Despite signs of stress, some cats exhibit more curiosity and a willingness to interact with their neighbours behind the glass. In a sense, the connections between these interacting cats are validated solely due to the properties of glass—both parties are perceptible only through visual and auditory means, without engaging other senses that might lead to further territorial conflicts.

Home and territory are not confined to geographical boundaries but are connected to ‘memorate knowledge’, which is ‘knowledge derived from individual experience unmodified by any socially shared or transmitted process as education’ (Peter J. Wilson in Aureli, 2019, pp.152). Like hunter- gatherer humans, cats roaming urban streets and household environments leave their marks on trees, walls, objects, and other species. This sociality appears highly fluid and unstructured from a human perspective. The dualistic separation of animate and inanimate no longer exists; they are all part of the living environment, within which a network is formed through various empirical trajectories of interactions.

This could also suggest a new way of mapping that explores the experiential aspects of how individuals interact with built environments, focusing on subjective experiences rather than scientific metrics. It involves validating cognitive approaches that ‘do not depend on the measuring parameters granted by science and technology, which in many cases are given to us by capital’(Aureli, 2019, pp.156), to examine how routines are sustained in built environments, and to ‘rediscover territories as existential grounds’(ibid.).

References

ASPCA. "Why Do Cats Knead?" ASPCA.org. Accessed September 1, 2024. Aureli, P.V. (2019) ‘TERRITORY’, AA Files, 76, pp. 152–155.

DePorter, T.L. et al. (2018) ‘Evaluation of the efficacy of an appeasing pheromone diffuser product vs placebo for management of feline aggression in multi-cat households: A pilot study’, Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, 21(4), pp. 293–305. doi:10.1177/1098612x18774437.

Eskilson, S. (2018) The age of Glass: A cultural history of glass in modern and contemporary architecture. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Fennell, C. (2015) ‘Introduction’, in Last Project Standing: Civics and sympathy in post-welfare Chicago. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 1–32.

Helliwell, C. (1996) ‘Space and sociality in a Dayak longhouse’, in Things as they are: New directions in phenomenological anthropology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Howell, P. (2015) ‘A Public Life for a Private Animal’, in At Home and Astray: The Domestic Dog in Victorian Britain. University of Virginia Press.

Latour, B. (2000) ‘The Berlin Key or How to Do Words with Things’, in Matter, Materiality and Modern Culture. Routledge, pp. 10–21.

RSPCA, Cat care tips, Advice & Health Information: RSPCA - RSPCA (no date) RSPCA. Available at: https://www.rspca.org.uk/adviceandwelfare/pets/cats (Accessed: 01 September 2024).

Miller, D. (2001) ‘Behind Closed Doors’, in Home Possessions: Material Culture Behind Closed Doors. Oxford: Berg, pp. 1–19.

Petridou, E. (2001) ‘The Taste of Home’, in D. Miller (ed.) Home Possessions: Material Culture behind Closed Doors. Berg. pp. 87-104.