Embodied disconnect: railroad infrastructure and peripherality in small-town Poland

Daria Duda

This essay explores the experiences of infrastructural exclusion and peripherality in small-town Poland by focusing on railroad infrastructure. I argue that after the capitalist transformation of the early 1990s, the withdrawal of the state from managing public transportation infrastructure caused it to decay and contributed to mobility disruption in non-metropolitan areas. Based on my fieldwork in the small Polish town of Prudnik I explore how the unreliable and fragmented train connections create a lived experience of disconnect and immobility for their users.

In this essay, I argue that the withdrawal of the state from managing and operating the railroad infrastructure in non-metropolitan Poland contributes to the peripheralization of small and middle-sized cities and their residents. I explore how the decaying, unreliable and fragmented network of train connections creates a lived experience of disconnect and immobility, based on a case study of the town of Prudnik. Employing phenomenological methodologies of embodied knowledge production, I investigate how political neglect and inequality is created through bodily interactions with the fragile and fallible railway infrastructure.

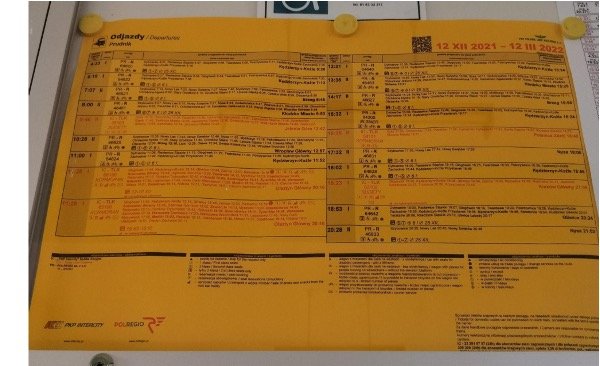

In the first section, I provide extensive socio-political and historical context in which the town of Prudnik can be placed. I proceed to explore the experiences of railway infrastructure in Prudnik using two focal points: the building of the Prudnik train station and the timetable of connections operated at the station. Through synthesizing my own embodied experiences of railway mobility in Prudnik and theoretical concepts from the fields of infrastructure anthropology and post-socialist studies I attempt to create a detailed image of experiences of peripherality in non-metropolitan Poland.

Contextualising the periphery: small and middle-sized towns in post-Soviet Poland

Figure 1. The regression of rail connections in Poland in the years 1988 - 2008. Source: Rosik et al., 2017, p. 116)

The post-Soviet model of development of the country was based on the dynamic development of large metropolitan centres: important, newly privatised companies and governmental agencies were moved to big cities, followed by a wave of economic migration from non-metropolitan regions (Śleszyński, 2018). This polarising model of development resulted in territorial disparities that continue to worsen as central cities grow and around half of 255 middle and small-sized cities are in danger of socio-economic collapse (IGiPZ PAN, 2017). What exacerbated the dire situation of non-metropolitan Poland was the new approach to transport infrastructure. Capitalist ideology centring on individual freedom gave rise to the focus on automotive infrastructure and supporting individual transport (Gitkiewicz, 2019, p. 33). Railroads were hit hard by this radical turn away from state-subsidised public transport. Once again, small and middle-sized towns were disproportionately affected by this process as local railroads deteriorated, resulting in regression of local passenger connections and eventual closing down of many local train stations (Rosik et al., 2017). While in 2005 there were still 1506 train stations operating in Poland, by the year 2015 the number shrank to just 519 (Poliński, 2016, p. 52 ).

Inhabitants of small- and middle-sized Polish towns, especially those with low income, unable to afford a car or too young or too old to drive one, found themselves ‘stuck’, unable to participate in the new consumer cultures centred in larger metropolitan centres (Burrell and Hörschelmann, 2014). In the light of this fact, I chose to centre the case study on the town of Prudnik and the remains of its railway infrastructure as it captures the complex entanglements of people, railroads, trains and stations in peripheral Poland.

My interest in Prudnik was piqued during the train journey from my hometown to the Gdańsk airport en route to London for university, reading Szymaniak’s (2021) brilliant book about so-called ‘collapse towns’, of which Prudnik is one of the first examples. The stories of the workers of the local textile factory that closed in 2010 after failing to survive the upheavals of the free market (Strauchmann, 2011) stayed with me, and I knew instinctively that I would make my way back to this small town.

Prudnik is located in the south of Poland, near the border with the Czech Republic. It has less than twenty-one thousand residents, a 12% unemployment rate (compared to 6% nationwide) and a rapidly ageing population (Polska w Liczbach, 2020). According to the analysis from 2017 (IGiPZ PAN, 2017), it sits at the top of the list of middle-sized Polish towns in danger of socio-economic collapse. The small train station in the town was built in the late 19thcentury. Currently, after many cuts in the early 2000s, it operates sixteen daily, mostly regional, connections (PKP, 2022). The reality of the failure to support the residents of peripheral Polish towns is very tangible within the space of Prudnik’s train station; it also manifests itself in the constant threat of mobility disruption, inevitable in the face of sparse, fragmented connections.

Theoretical background

Infrastructures have proven to be a useful and unique locus of anthropological inquiry, allowing researchers to explore how the otherwise abstract entity of the state interacts with its citizens through the materiality of the everyday functioning of systems such as roads, railways, water pipes and electrical cables (Harvey and Knox, 2015; Larkin, 2013). Infrastructures, especially spectacular developments, are used by the state to construct material narratives of progress. However, by paying close attention to the political and material lives of infrastructures, practices and processes such as decay and neglect can be uncovered, revealing the ‘fragile and often violent relations between people, things, and the institutions that govern them’ (Appel, Anand and Gupta, 2018, p. 3) This way of seeing infrastructures as sites of reproduction of state power through material practices has been used in particular to shed light on the experiences of urban marginality of precarious populations of global metropolises (Alda-Vidal et al., 2018; Anand, 2020; Baptista, 2019). Using these conceptual frameworks to write about small-town Poland might seem farfetched. However, I believe that the same political processes govern the production of disconnect in peripheral Polish towns such as Prudnik. It is these political practices of neglect and differential provisioning that I seek to uncover in this essay by focusing on the materiality of infrastructures through which they are realised.

Because my case study explores the railway infrastructure as a locus of political interactions between the Polish state and its citizens, I substantiate my research with the expertise from the field of post-socialist material culture studies. In the literature about post-Soviet countries, particular attention is paid to the remains and ruins of the built environment constructed in the style of social modernism, which became synonymous with the political project of communist modernity (Bennet, 2021; Martin, 2014). Looking at what became of socialist infrastructure can reveal the particularities of growth and decay that took place in the 30 years since the collapse of the Soviet bloc, helping to put the conditions of capitalist peripherality in historical context.

In this essay, I apply phenomenological methodologies to my exploration of infrastructure. Phenomenologists centre the body as the locus of human engagements with the surrounding world (Tilley, 2004). This allows for exploring embodied entanglements of humans with the material landscapes they are moving through, discovering how material objects actively produce the reality in which we are enmeshed through acting on our bodies (Spyer, 2012). Following from Knox (2017), I believe that paying attention to the affective, embodied relationships that people experience with material forms is a perfect starting point for exploring how the political power of the state is enacted through those material forms and experienced by people through their mundane, everyday activities. Therefore, in this essay, I substantiate my claims with the data collected during my two field trips to Prudnik (in December 2021 and January 2022), which take the form of snippets of multisensorial ethnographies of Prudnik’s train station and train connections.

The landscape of decay, the landscape of progress

The way that the interactions of humans and infrastructural materiality can be looked at is through the infrastructure's life (Graham and McFarlane, 2015). Different phases in the life of infrastructures include destruction, decay, maintenance, rebuild and repair (Ramakrishnan, O’Reilly and Budds, 2020). Thinking of infrastructure in terms of its lifetime allows us to consider its temporal fragility (Ramakrishnan, O’Reilly and Budds, 2020): the ways in which infrastructural systems eventually decay and break down, and the contingent affective experiences of exclusion and inequality resulting from this process. In the post-Soviet reality of rapid privatisation of state-owned enterprises and a massive reduction in public spending, the state’s withdrawal from the maintenance of public transport infrastructure became the norm, causing many Polish local train stations to slowly decay and fall into ruin due to lack of investment.

The lack of maintenance of Prudnik’s train station and its surroundings normalises a state of disrepair, making the landscape of decay, crumbling stone, rusting railings and exposed wires a landscape of Prudnik’s residents' daily movements. This stands in sharp contrast with metropolitan train stations, such as the one in Wrocław from which I take the train back to my hometown. Open spaces, glass and steel - essential materials of spectacular infrastructure meant to elicit associations of modernity and progress (Larkin, 2013; Mrazek, 2002) - complement the original building of the 19th-century train station, restored in preparation for Euro 2012 hosted in Poland and Ukraine (Sarna, 2014). Meanwhile, in Prudnik, the original 19th-century railway infrastructure is crumbling and falling apart. The German-built brick building of the passenger station is closed with bars in the windows and a clock that must have stopped decades ago. In Wrocław, the original awning over the platforms has been renovated and passengers can now marvel at the unique steel construction. In Prudnik, live wires are hanging from the holes in the awning over the heads of passengers (Madrjas, 2019). The landscape of decay of the Prudnik station is a material representation of the Polish state’s absence and neglect of peripheral regions, as the dereliction and hostility of a local train station starkly juxtapose the sleek cleanliness of the metropolitan train station. The contrast between local train stations and their metropolitan equivalents shows that modern ruins in post-socialist countries do not necessarily indicate a lack of development but unequal investment provisioning, brought about by the harsh reality of emergent capitalist markets.

The future without: when a station is not a station

The inside of Prudnik station, which is the small part of a waiting room that is open for access, has its own story of abandonment embedded in its material form. The interior, modernised during the times of the Polish People’s Republic in the characteristic, socialist-modernist style, is now visibly decaying, creating a particular reality of post-socialist emptiness that can only be experienced in former Soviet-bloc countries. Dzenovska (2020) describes post-socialist emptiness in the context of Latvian villages as a social formation wherein ‘places rapidly lose their constitutive elements such as functions, services and people’ (Dzenovska, 2020, p. 10). The visual assault of the past [SB1] inside Prudnik’s waiting room is compounded by the multisensory experience of moving through its empty space. As I walk in, my steps reverberate loudly in the unsettling silence, making the space of the waiting room seem bigger than it is. There is no heating, so the winter air inside the room is bone-chillingly cold and smells icy and sharp. Since the room provides no shelter, I decide to wait for the train outside and as the scheduled time of departure draws close, I realise that other people at the station are also choosing to wait on the platform. At that moment, I realise that this building is not a train station, even though it looks like one (Lea and Pholeros, 2010): its emptiness has pushed people away as the space is too uncomfortable to fulfil its function. Instead, the unchanged form of the waiting room makes it a living fossil, a relic of the past signalling the impossibility of change. Inside Prudnik’s train station, post-socialist emptiness is tangibly connected to the imagining of a ‘future without’ (Dzenowska, 2020). Systematic decay of post-Soviet architecture creates a spatio-temporal narrative of disappearing: just as the populations of peripheral towns deplete and age, the infrastructure connecting them with the outside world decays, implying that one day it will cease to exist.

Possibility of breakdown, mobility strategies and invisible labour of visible infrastructures

In her work about Vietnamese water pipe systems, Schwenkel (2015, p. 520) writes that ‘breakdown as routine means a certain routine of breakdown’, generating innovation and improvisation, but also additional labour and dissatisfaction with the local government in charge of maintaining the water infrastructure. I would contend that in the case of Prudnik’s railway, this routine emerges way before the actual breakdown occurs, stemming from the very real possibility of breakdown. In the case of Polish local rail transport, the promise of mobility is compromised by the shadow of uncertainty and possible disruption of flow. The Polish company operating train connections, PKP, is notorious for its delays: in 2021, only 66,12% of its trains arrived on time with an average delay of 21 minutes (Madrjas, 2021).

The precarity of mobility is felt particularly severely by residents of peripheral Polish towns, where passengers are more likely to take multimodal, multi-stage transportation routes (Rosik et al., 2017). Preparing for these routes generates a kind of invisible labour that often gets overlooked when thinking about mobility. Constant strategizing, being prepared for the breakdown of the itinerary, making sure to leave a window of time for potential delays, making split-second decisions to change the mode of transport used: all this is a part of daily mobility strategies for peripheral Poland residents. This overall condition of uncertainty makes itself visible in bodily habits that I observe at the Prudnik station, among my co-passengers and in myself: constant checking of the time, looking and listening for the train down the railroad, omnipresent pacing. All this effort that goes into making mobility possible in the face of fallible train connections demonstrates the hypervisibility of infrastructure as it is experienced in Prudnik. It demonstrates that infrastructural invisibility is not merely a result of its smooth functioning: it is a political condition, experienced by those in privileged, hegemonic positions (McFarlane, 2008). For those belonging to more precarious social groups, such as the peripheralized residents of non-metropolitan Poland, the infrastructures are necessarily in the foreground, requiring expert strategies to navigate them.

Constructing remoteness through waiting: spatio-temporal dilation

Transportation infrastructures have a unique power to modify the very experience of time and space (Dalakoglou and Harvey, 2012; Harvey, 1990). Historically, railroads and trains have contributed to the compression of time and space, shooting through the landscape with newfound speed, connecting populations previously disconnected (Harvey, 1990). However, erratic and unreliable rail transport can also construct remoteness as in Mc Callum’s [SB1] [DD2] (2018) work on railway infrastructure in Buenos Aires. In Prudnik, this infrastructural remoteness results particularly from fragmentation, as train connections are so organised as to not cross regional administrative borders. Regional connections in Poland are managed and operated by regional authorities, on the administrative level of voivodeships, meaning that the connections are often delineated not to cross the voivodeship borders and they just break off in the towns near the border (Gitkiewicz, 2019; Górny, 2016). The fragmented nature of the connections means that destinations on the other side of the voivodeship border get pushed away, as the journey towards them is made longer by the necessity to stop at the intermediate stations.

Wrocław, a major city in the voivodeship adjacent to Prudnik’s makes for one of these pushed away destinations. There is one direct connection between Prudnik and Wrocław: other than that, passengers have to change trains in Nysa or Brzeg. That is how I found myself stuck at the tiny train station in Brzeg, worrying that this time I won’t catch the train home, departing from Wrocław in just under an hour. My train from Prudnik to Brzeg arrived at its destination on time; however now the train to Wrocław, operated by a different company, was getting 10, 15 and eventually 30 minutes late. The journey could have lasted 2 hours, but now is broken up by an hour of waiting in Brzeg, just four stops away from Wrocław. Waiting, such an essential part of navigating the fragmented railway network feels cold (because the train station, although beautifully renovated, has no heating), smells like cigarette smoke (wafting through a window that cannot be closed) and sounds like incomprehensible train station announcements that my co-passengers and I are desperately trying to make sense of. In these stressful moments, I can physically feel the distance between me and Wrocław get dilated, elongated beyond the physical mileage. The fragmented infrastructure dictates the passengers’ affective experience of the distance between Prudnik and Wrocław, driving the two locations further away from each other.

Figure 20. The route was taken by me from Prudnik to Wrocław through Brzeg. Source: Google Maps, 2022. Available at: www.google.com/maps/place/Prudnik,+Polska/

Conclusion

The neglect and fragmentation of railway infrastructure in Prudnik perfectly encapsulates the ways in which the Polish state has failed small towns and their residents in the decades since 1989. Transportation infrastructure that in its design has the primary function of enabling mobility, in this case, perpetuates conditions of marginalisation and disconnect. The building of the train station slowly falls into complete dereliction, careening towards disuse and creating a narrative of disappearing. Precarious and sparse connections force Prudnik’s residents to operate their daily itineraries in the shadow of constant mobility disruption, while simultaneously driving the town further away from nearby cities and their promise of growth. From the platforms of the Prudnik train station, the future of peripheral Poland and its citizens’ mobility looks grim. If the state continues its politics of neglect and abandonment, train station buildings will continue to decay and connections will continue to disappear, exacerbating the already incredible disparity between metropolitan and non-metropolitan parts of the country.

References

Alda-Vidal, C., Kooy, M. and Rusca, M. (2018). ‘Mapping operation and maintenance: An everyday urbanism analysis of inequalities within piped water supply in Lilongwe, Malawi’, Urban Geography, 39(1), pp. 104–121.

Appel, H., Anand, N. and Gupta, A. (eds.) (2018). The Promise of Infrastructure. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Anand, N. (2020). ‘After Breakdown: Invisibility and the Labour of Infrastructure Maintenance’, Economic and Political Weekly, (December), pp. NA.

Baptista, I. (2019). ‘Electricity services always in the making: Informality and the work of infrastructure maintenance and repair in an African city’, Urban Studies, 56(3), pp. 510-525.

Bennett, M. M. (2021). ‘The Making of Post-Post-Soviet Ruins: Infrastructure Development and Disintegration in Contemporary Russia’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 45(2), pp. 332-347.

Burrel, K. and Hörschelmann, K. (eds.) (2014). Mobilities in Socialist and Post-Socialist States: Societies on the Move. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dalakoglou, D. and Harvey, P. (2012). ‘Roads and Anthropology: Ethnographic Perspectives on Space, Time and (Im)Mobility’, Mobilities, 7(4), pp. 459-465.

Dzenovska, D. (2020). ‘Emptiness’, American Ethnologist, 47, pp. 10-26.

Gitkiewicz, O. (2019). Nie zdążę. Warsaw: Dowody na istnienie.

Górny J. (2016). ‘Samorząd wojewódzki jako organizator kolejowych regionalnych przewozów pasażerskich’, Prace Komisji Geografii Komunikacji PTG, 19(4), pp. 72-81.

Graham, S. and McFarlane, C. (eds.) (2015). Infrastructural lives: Urban Infrastructure in Context. Abingdon-on-Thames: Rutledge.

Harvey, D. (1990). The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Harvey, P. and Knox, H. (2015). Roads: An Anthropology of Infrastructure and Expertise. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Instytut Geografii i Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania PAN (2017). 122 miast średnich tracących funkcje społeczno-gospodarcze. Available at Accessed: 19 January 2022).

Knox, H. (2017). ‘Affective Infrastructures and the Political Imagination’, Public Culture, 29(2), pp. 363-384.

Larkin, B. (2013). ‘The politics and poetics of infrastructure’, Annual Review of Anthropology, 42, pp. 327-343.

Lea, T. and Pholeros, P. (2010). ‘This is not a pipe: The treacheries of indigenous housing’, Public Culture, 22(1), pp. 187-209.

Madrjas, J. (2021). ‘Kolej opóźniona. Tak źle z punktualnością nie było od lat’, Rynek Kolejowy, 15 November. Available at: https://www.rynek-kolejowy.pl/mobile/kolej-opozniona-tak-zle-z-punktualnoscia-nie-bylo-od-lat-105357.html (Accessed: 19 January 2022).

Madrjas, J. (2019). ‘Wiata w Prudniku dalej czeka na remont’, Rynek Kolejowy, 7 January. Available at: https://www.rynek-kolejowy.pl/mobile/wiata-w-prudniku-dalej-czeka-na-remont-90076.html (Accessed: 19 January 2022).

Martin, D. (2014). ‘Debates and Developments’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(3), pp. 1037-1046.

Mc Callum, S. (2018). Derailed: Ageing railroad infrastructure and precarious mobility in Buenos Aires. Ph. D. Thesis. University of California Santa Cruz. Available at: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2zt247kj (Accessed: 19 January 2022).

McFarlane, C. (2008). ‘Governing the Contaminated City: Infrastructure and Sanitation in Colonial and Post-colonial Bombay’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 32(2), pp. 415-435.

Mrazek, R. (2002). Engineers of Happy Land: Technology and Nationalism in a Colony. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

PKP (2022). Plakatowy rozkład jazdy: Prudnik. Available at: https://portalpasazera.pl/Plakaty (Accessed: 19 January 2022).

Poliński, J. (2016). ‘Dworce we współczesnym transporcie kolejowym’, Prace Instytutu Kolejnictwa, 150, pp. 51-58.

Polska w Liczbach (2020). Prudnik w liczbach. Available at: https://www.polskawliczbach.pl/Prudnik (Accessed: 19 January 2022).

Ramakrishnan, K., O’Reilly, K. and Budds, J. (2021). ‘The temporal fragility of infrastructure: Theorizing decay, maintenance, and repair’, Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 4(3), pp. 674-695.

Rosik, P., Pomianowski, W., Goliszek, S., Stępniak, M., Kowalczyk, K., Guzik, R., Kołoś , A. and Komornicki, T. (2017). Multimodalna dostępność transportem publicznym gmin w Polsce. Warsaw: PAN IGiPZ.

Sarna, B. (2014). ‘Nieznany Wrocław – kolejowa perła dworzec Wrocław Główny’, Wrocław.pl, 7 April. Available at: https://www.wroclaw.pl/nieznany-wroclaw-kolejowa-perla-dworzec-wroclaw-glowny (Accessed: 19 January 2022)

Schwenkel, C. (2015). ‘Spectacular infrastructure and its breakdown in socialist Vietnam’, American Ethnologist, 42, pp. 520-534.

Spyer, P. (2012). ‘The body, materiality and the senses’, in Tilley, C., Webb, K., Kuchler, S., Rowlands, M. and Spyer, P. (eds.) Handbook of material culture. London: SAGE, pp. 125-129.

Strauchmann, K. (2011). ‘Historia firmy Frotex’, Nowa Trybuna Opolska, 23 September. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20171120020010/http://opolskie.regiopedia.pl/wiki/historia-firmy-frotex (Accessed: 19 January 2022).

Szymaniak, M. (2021). Zapaść. Reportaże z mniejszych miast. Wołowiec: Czarne.

Śleszyński, M. (2018). Polska średnich miast. Założenia i koncepcja deglomeracji w Polsce. Warsaw: Klub Jagielloński.

Tilley, C. and Bennet, W. (2004). ‘From Body to Place to Landscape: A Phenomenological Perspective’, in Tilley, C. The Materiality of Stone: Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology. London: Routledge, pp. 1-32.