Breaking the Glass Ceiling: Women’s Rights to Urban Spaces in Pakistan

Hawwa Faruque

This essay employs an interdisciplinary approach of gender, space and the built environment to explore how gendered narratives are embodied and reproduced within the homes and urban spaces of Pakistan. In particular, it highlights how the spatial practices of women are largely constricted to the private sphere. Considering the role of history and religion, we see how gendered narratives are reproduced in the home, and also, how the social implications of the city’s infrastructure impact women’s mobility. However, with recent feminist initiatives that insert women into public narratives, there is potential for women to reclaim the ‘rights’ to their city.

“Rights are not experienced in the abstract but have a spatial and material dimension” (Beebeejaun 2016 p. 324)

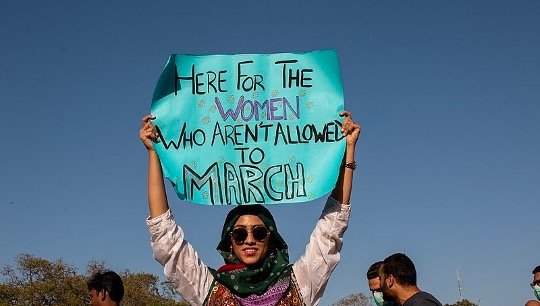

Beebeejaun’s observations on the substance of rights articulates the notion of a gendered and embodied citizenship that is inherent in the country of Pakistan, whereby the spatial practices of women are governed by a principle of relegation to the private sphere. These spatial restrictions have prompted political acts such as the Aurat (Women) March held in the city of Karachi on 8 March 2020, in the spirit of International Women’s Day. Women assembled themselves outside a public landmark in an effort to protest issues pertaining to gender inequality. Living in a conservative country where their presence is largely marginalized to the private sphere, one of the most pertinent concerns they put forward was their right to simply exist in public spaces.

Using theoretical perspectives related to gender, space and the built environment, I seek to demonstrate how the city’s built environment holds potential to embody cultural values and imply standards of behavior that, in turn, reproduce gendered narratives that constrict women’s freedom of mobility. Through exploring anthropological approaches to the home, as well as infrastructure, I argue that in enabling the embodiment of gender roles, the built environment forms gender segregated sites that work to subvert and marginalize women’s social position within society.

Ghar and Bahir

In order to understand the rigid gender dynamics and spatial practices prevalent in Pakistan, it is important to contextualize them within the rich social and political history of the country. In 1947, after the British withdrew from India, the modern state of Pakistan was created, amalgamating the Muslim-majority regions of the country. British colonialism had left a profound impact on the Indian Muslims, and the reason they desired to make a Muslim majority state was “to preserve and foster Islamic values”(Choudhury 1957). The country has long since followed a conservative ideology that is largely characterised by a respect of tradition, adherence to rule of law and an ideation to the religion of Islam.

The country’s conservative ideology can be traced back to the period of the British colonial rule in India. For the colonized and oppressed people, upholding their spiritualist traditions and nationalist sentiments offered a way out of colonialism, as they sought pride in the belief that “in the spiritual domain the East was superior to the West” (Chatterjee, 1989, p. 623). While they imitated the West in the public sphere, what could not be colonized was the home and their women’s values. By keeping the Indian woman within her home, her self-identity would be preserved and protected and hence the “distinctive spiritual essence of the nationalist culture” as well (Chatterjee, 1989, p.623). Thus, gendered ideals rooted within Indian culture, associating women with respect, privacy and modesty came to be intertwined with the home and its intimacy.

The juxtapositions between the home and the public sphere, to which the terms ghar and bahir correspond, formed a symbolic contrast that aided in the formulation of the nationalist project. ‘Ghar’ (home) was seen as a protective shell, preserving the sanctity of the woman from the “treacherous terrain” of the public sphere. “The home in its essence must remain unaffected by the profane activities of the material world- and woman is its representation” (Chatterjee 1989, 239). The rigid distinction between the private and public sphere was dichotomised into notions of material and spiritual. While the outside world in its ‘materiality’ was tarnished by effects of colonization, the spiritual sphere of religious and cultural traditions remained untouched and intact. The privacy of the home in British Indian culture came to be seen as holding a certain sacred essence, “the home represents our inner spiritual self, our true identity”(Chatterjee 1989, 239).

Lévi-Strauss’ theory of the ‘house society’ perfectly elucidates this spiritual agency of the home. He positions the home as a collective form of moral personhood which embodies the reproduction of social relations. Through this lens, the house in its materiality is a vehicle for the self- realization and actualisation of persons and identities: “people construct houses and make them in their own image, so also do they use these houses and house-images to construct themselves as individuals and as groups” (Carsten & [SB1] Hugh-Jones 1995, p.3). This theory is also demonstrated in the fact that the traditional subcontinental home was constructed as a reflection of Islamic values. Since women are held to a high standard of respect in Islam, local architecture needed to conserve their privacy. One of the architectural elements of the home, the jaali, which was a perforated screen, thus posed to directly represent the veil. It permitted women their privacy as they could speak to someone on the other side without having to reveal themselves.

Figure 3. Jaali

This embodied form of reservation acted as a symbolic shelter from the outside world, as well as a reflection of their gendered religious values. In this sense, the characterisation of the home can be seen as an extension of the identity of its inhabitants. The homes signify much more beyond themselves, bearing the meanings of social and cultural signs that are reproduced within them.

The dichotomy between ghar and bahir can also be linked to the religion of Islam. However, the Islamic conceptualisation is mainly contextual and not as rigid as the cultural practices that are based on it. The constituents of public and private are based on the Islamic notion of Na-Mahram and Mahram. The former points to the categorisation of people “into those of the opposite sex with whom marriage is permitted” and the latter “with whom marriage is explicitly forbidden” such as siblings and parents(Mazumdar and Mazumdar 2001, p. 302). Hence, for practicing Muslim women the sharing of space with Na-Mahram becomes problematic.

In the traditional Pakistani home, when Na-Mahram male guests enter, the space is re-conceptualised as public. A front room or baraamda poses as an accessible public area where the men of the household and the male guests can socialize with each other. In traditional upper-middle class homes, there are several rooms set aside as ‘public’, and there are often also specific ‘guest rooms’. This is to ensure that the rest of the house remains private, and there are also usually separate entrances in all the rooms, so women do not have to interact with guests (Mazumdaar and Mazumdaar 2001). In the case of lower middle class families, where there may be only one room in the house, the nature of the space may be promptly transformed from an internal family room to an external area to greet guests, as the women leave the room. Here, notions of public and private are more symbolic than physical, as curtains and screens are used to demarcate the public and private, “emphasizing the improvisational nature of space” (Mazumdaar and Mazumdaar 2001, p. 304).

Using Bourdieu’s notion of habitus, we see how these spaces within the home are symbolically charged and defined by the bodily performance and routine of women as they enter and leave the rooms(Bourdieu and Nice, 2013). The home and its structural divisions are imbued with meaning, which is contingent on the shifting movements and perspectives of its inhabitants. In turn, the social implications of the configurations of the home push to compel women into a certain routine of ‘gender performances’ (Butler, 1988) that subvert their freedom of mobility in space. Here, we see the home in respect to how the gendered bodies within it are taught to move; this internalization of bodily routine aids in the reproduction of current gender binaries. This, in turn, demonstrates how the transformative nature of the built environment aids in the categorisation and construction of gender identities, which sheds light on the processes through which the gendered narratives of ghar and bahir are enforced.

Negotiating the City

In his anthropological analysis of infrastructure, Larkin demonstrates the ways in which the underlying material structures of a city are instrumental in constructing modes of sociality as they “generate the ambient environment of everyday life”( 2013, p. 328)., Similarly, in an essay tiltled What Would a Non-Sexist City Be Like? (1980), Dolores Hayden illustrates how urban planning and architectural design are instrumental in constraining women’s equal participation in social and economic life. Similarly, scholar Beebeejaun points towards the socially constructed geographical and architectural arrangements that constrict women's access and mobility in city spaces, as they form sites to assumptions about gender.

This is due to the fact that discourses of city planning generally assume the user of public space to be a neutral citizen, whereas, in reality, urban planners have created gendered environments suited to the needs of men and the traditional heteronormative family. In Pakistani cities, such as Karachi, the residential area is usually situated away from the production area, and the production area, in turn, is distant from spaces of leisure: “In metropolitan cities like Karachi, zoning is done in ways that completely ignores the element of gender inclusion. Our zoned cities divided housing, working, public spaces etc. into separate locations; for example, our residential, commercial and industrial zones are at large stretches from each other which can create problems for women to travel long distances for duties” (Ejaz et al., 2021, p. 11).

Hence, these architectural and spatial components impact women’s mobility, and illuminate the existing conditions of the city as gendered networks. Physical elements of the built environment, such as distance, access, and connectedness structure the bodily routine and performances of women, and work to reproduce gender differentials. Jos Boys (2017) explicates this notion as she illustrates how urban planning itself is complicit in segregating women from the rest of the city, as the architectural space functions as a physical manifestation of social relations. The physicality of these gendered zones, and their stifling patriarchal implications, constitute the visible and invisible boundaries which enforce women’s limited mobility in the city.

Furthermore, in a study conducted in a low-income neighborhood of Lyari in Karachi, it was found that women spatially inhabit a city differently than men, who are seen as the ‘default user’ of the patriarchal society (Adnan, 2019). They “negotiate the city differently and also perceive the boundaries of space differently” (citations required). Phadke (2007) exemplifies this as she highlights how certain elements of the city’s infrastructure warrant differential gender access, as they may pose as daunting to women. According to a survey, 55.7% of women were in agreement over the fact that the infrastructure of Pakistani cities is not aligned to their diverse needs, wants, or even physical requirements (Ejaz et al., 2021, p. 8).

As outlined in the Feminist Inquiry into Urban Planning (2021), there is a need to consider the social implications of city planning for women. Otherwise, Pakistan will continue to have one of the most male-dominated spaces in the world (Compendium on Gender Statistics of Pakistan 2019 | Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, 2022). Phadke illustrates how women’s experiences in urban spaces are not only rendered problematic due to ‘unfriendly’ individuals but ‘unfriendly’ spaces (2013).Due to the incompetency of urban planners, women face intimidating spatial contexts, such as inadequate lighting and broken sidewalks, which significantly impact their safety and movement. The characterisation of the streets by women as ‘dangerous’ feeds into the gendered narrative of ghar and bahir as women internalize the notion that public spaces are forces of masculinist transgressions. It is to this reason that some women choose to wear larger veils in public, that cover their whole body rather than just their head, thus maximising spatial protection;in other words, they look inward for safety that their built environment does not provide. Therefore, we should understand the built environment not simply as structures plugged onto a site devoid of social implications, but instead as a reflection of the social and political forces imprinted onto it. We can see this through the lens of Lefebvre (1974), who argues, in his critique of current architectural and spatial practice, that an improved review towards social space can bring about diversity and uniqueness. By taking into consideration the differential gendered experiences in the city, we can work towards making the city spaces more ‘friendly’ for women.

Rights to the city

The concept of the ‘rights to the city’ was first coined by French philosopher Henri Lefebvre as he theorized that, as social spaces are defined by the reproduction of human relations, these spaces hold the potential to be redefined, thus “permit(ting) fresh actions to occur” (1991, p. 73). In further explication of this notion, David Harvey wrote “The right to the city is far more than the individual liberty to access urban resources: it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city.” (citation required)

I use this notion to shed light on the current new wave of socio-political feminist movements that call for the un-gendering of Pakistani cities by encouraging women to insert themselves in public spatial narratives. Every year, on International Women’s Day, Pakistani women call for an Aurat March in solidarity of their equal rights, where they protest in a public space. “We need to reclaim our parks, streets, our public transportation, and we need to be visible… we can’t be hiding in our homes any longer” (Saleem, 2019). Another feminist initiative, Girls at Dhabas also raises the conversation of women’s engagement in the public sphere. Dhabas, which is loosely translated to roadside restaurants, are traditionally male-dominated domains. The simple act of an unaccompanied female sitting at a dhaba is perceived as transgressive. On their website, the initiative states, “Girls at Dhabas is a collective of feminists who are concerned by the disappearance of women from public spaces, and seek to re-imagine a world where all genders have equal and unquestionable access to public spaces” (Saleem, 2019). The idea behind these initiatives are that re-situating women’s bodies away from homes into public spaces re-conceptualises the city’s landscape, and defies the gendered construction of ghar and bahir.

In his explanation of the ‘rights to the city’ Harvey discusses the prospect of revolutionary social change by way of gaining greater control over the way the city is formed as a collective. For him, urban space is about power and the struggles for its territorial control are directly connected to the politics of identity. According to Beebeejaun (2016), a city is gendered through multiple actions and experiences of its inhabitants. Traditionally, women within urban spaces have had to ‘demonstrate a purpose’ for their presence, such as waiting for the bus, or buying food at the market. Hence, Phadke et al suggest that the act of loitering by women in public spaces works to “subvert the performance of gender roles”, as it challenges the rigid gendered assumptions between the divide of ghar and bahir (Phadke et al, 2011). It is a claim over the city using women’s bodies and also a re-writing of gendered narratives. Hence, feminist interventions in the public sphere such as Aurat March and Girls at Dhabas work towards changing the gendered assumptions that are attached to urban sites and form the basis for revolutionary social change.

Conclusion

As demonstrated in this essay, a built environment approach aids in understanding how city spaces in Pakistan are gendered in terms of access, networks and zones. Through an anthropological lens on the home, we can see the role of social history and religion in reproducing gendered narratives within the built environment. Furthermore, we highlight how the social implications of the infrastructural elements within the city greatly impact women’s freedom and safety of movement. In conclusion, using Lefebvre’s notion of the ‘rights to the city’ I argue that, as the identity of these urban spaces are seen as contested, unfixed and multiple, there is potential for women to reclaim the city by inserting themselves into the public narrative, which works to subvert traditional gender norms.

REFERENCES

Adnan, J., 2019. The Missing Half: Reintegrating Women Into Pakistan’s Public Spaces in Lyari, Karachi. Ph.D. Dalhousie University.

Beebeejaun, Y., 2016. “Gender, urban space, and the right to everyday life.” Journal of Urban Affairs, 39(3), pp.323-334.

Bourdieu, P. and Nice, R., 2013. Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Boys, J., 2017. Disability, space, architecture. London: Routhledge.

Butler, J., 1988. Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory. Theatre Journal, 40(4), p.519.

Carsten, J. and Hugh-Jones, S., 1999. About the house. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chatterjee, P., 1989. “Colonialism, Nationalism, and Colonialized women: the contest in India” American Ethnologist, 16(4), pp.622-633.

Choudhury, G. W., 1957. “The Impact of Islam in Pakistan.” Current History 32, no. 190 pp. 339–44. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45309731.

Ejaz, A., Gulzar, B., Qadri, G., Zaidi, I., Muluk, S. and Zia, Z., 2022. Feminist Inquiry into Urban Planning. [online] Learnersrepublic.com. Available at: <https://learnersrepublic.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/A-Feminist-Inquiry-Into-Urban-Planning.pdf> [Accessed 15 January 2022].

Harvey, D., 2008. “The Right To The City”. The New Left Review, (53), pp. 23-40. https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii53/articles/david-harvey-the-right-to-the-city

Hayden, D., 1980. What Would a Non-Sexist City Be Like? Speculations on Housing, Urban Design, and Human Work. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 5(S3), pp.S170-S187.

Larkin, B., 2013. The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure.

Lefebvre, H. (1991) The production of space. London, England: Blackwell.

Mazumdar, S., Mazumdar, S., 2001 “Rethinking Public and Private Space: Religion and Women in Muslim Society.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 18, no. 4 : 302–24. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43031047.

Medium. 2022. In Focus — Girls at Dhabas: Redefining public spaces for women in Pakistan. [online] Available at: <https://medium.com/samata-joshi/in-focus-girls-at-dhabas-redefining-public-spaces-for-women-in-pakistan-2b6170cbbe59> [Accessed 14 January 2022].

Pbs.gov.pk. 2022. Compendium on Gender Statistics of Pakistan 2019 | Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. [online] Available at: <https://www.pbs.gov.pk/content/compendium-gender-statistics-pakistan-2019> [Accessed 16 January 2022].

Phadke, S., Khan, S. and Ranade, S., 2011. Why loiter?. New Delhi: Penguin Books.

Saleem, S., 2019. Aurat March 2019 brings diverse voices to the spotlight. The News, [online] Available at: <https://www.thenews.com.pk/magazine/instep-today/442463-aurat-march-2019-brings-diverse-voices-to-the-spotlight> [Accessed 14 January 2022].